“It’s a pretty important year,” Wilkinson told Calgary Herald columnist Chris Varcoe, more than three years Pathways first proposed the mammoth project.

“We need to stop pushing this out,” he added. “We need to fish or cut bait soon.”

A ‘Foundational’ Project

The Pathways Alliance has long touted carbon capture and storage (CCS) as the technology that will enable its six members, which account for about 95% of Canada’s oil sands output, to continue and expand production in a low-carbon world. If it’s ever built, the carbon capture hub that Pathways calls a “foundational” project will store about 10 to 12 million tonnes of carbon per year, a small share of the 86.5 megatonnes of direct emissions the oil sands produced in 2022, according to the federal government’s annual emissions inventory. (That calculation doesn’t factor in the roughly 80% of the emissions in a barrel of oil that occur after the product reaches its end user.)

And that’s only if it delivers as advertised. In September 2022, IEEFA concluded that 10 of the world’s 13 “flagship, large-scale” CCS projects had fallen short of expectation, with seven of them underperforming, two failing outright, and one of them mothballed.

IEEFA also reported CCS operators were selling off nearly three-quarters of the carbon dioxide they captured each year for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), a process by which CO2 is injected into depleted wells to extract more oil. In November 2023, the federal government stepped back from a pledge that taxpayer subsidies would exclude CCS projects devoted to EOR.

Around the same time, the Regina-based International CCS Knowledge Centre acknowledged it would be extremely difficult for CCS to meet a 2035 decarbonization deadline based on the current state of the technology. “This blows my mind,” IEEFA analyst David Schlissel said at the time. “It’s hypocritical. These guys have been hyping 90%, 95% capture, and now it’s, ‘well. we really can’t do it that fast, it’s not tested, it’s not certain’.”

Costs ‘Spiralling’, Revenues Uncertain

Based on the two Alberta CCS projects already in operation, IEEFA headlines [pdf] that carbon capture costs in the province “are spiralling upward—with no commensurate increase in productivity—and may already be underestimated.” At Shell Quest, the price per tonne rose from $34.70 to $62.54 between 2016 and 2023. At ACTL, which captures CO2 from a Nutrien fertilizer plant in Redwater, Alberta, the cost increased from $30.44 to $49.25 between 2020 and 2023. In both cases, actual operating experience exceeded the cost increases in the companies’ economic modelling.

“Although there is always the possibility that cost efficiency could improve in future years, such an assumption likely would be unduly optimistic, since such efficiency gains have yet to materialize after almost a decade of operations at Quest and four years at the ACTL,” IEEFA writes. “The Pathways project will likely have to deal with similar challenges of escalating energy, material, and labour costs. If operating costs rise at currently observed industry rates for the life of the project, then total cost per tonne of CO2 at the proposed facility would balloon to levels that make breakeven or profitability highly improbable.”

Pathways will also find it difficult to make enough money to break even, much less turn a profit, IEEFA adds. Under Alberta’s emission performance credit (EPC) system, a project like Pathways stands to derive most of its revenue by selling credits to big industrial emitters that need them to meet their own carbon targets. But the provincial system provides no incentive for emitters to pay more than the prevailing carbon price for emissions credits.

That price currently stands at $80 per tonne, the federal climate plan currently calls for the price to top out at $170 in 2030—and IEEFA makes no mention of the strong likelihood that the carbon pricing system as a whole will be dismantled after this year’s federal election. But even if $170 eventually became the ceiling price for a tonne of carbon, the report stresses that there’s no minimum price. If the large number of carbon capture proposals now under consideration in Alberta leads to an oversupply of emissions credits, their cost will fall—which means the Pathways project “could generate far less revenue for each tonne of net CO2 captured.”

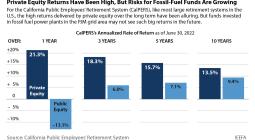

Which might explain why Pathways members have been lobbying relentlessly for more lavish government subsidies for the project, even through the recent years when they were raking in record profits.

Shareholders Won’t Subsidize CCS

“Permanently subsidizing a risky, unproven, and high-cost venture… is unlikely to be an attractive proposition to their shareholder,” IEEFA writes. “The prospect of negative-to-marginal returns is hardly a magnet for investor capital, and management decisions to invest in sub-optimal projects are unlikely to boost market confidence or win shareholder votes. This might explain why—despite near record cash flow and sky-high profits—the oil sands industry continues to lobby government officials for additional financial support for the project.”

Report author and IEEFA Energy Finance Analyst Mark Kalegha said those risks appear to be weighing on industry decision-makers. “It is evident that Pathways Alliance and the broader industry have reached this same conclusion,” he told The Energy Mix in an email. “I base this on the level of subsidies that have been advanced to current operational CCS projects in the province (between 50 and 90% of lifetime operational and capital expenditure) as well as ongoing requests by Pathways for additional government support—despite already very generous and significant levels available.”

But with the Canada Growth Fund “set to announce some additional measures that could have material effects on the economics of the project,” he added, Pathways’ final investment decision “can go either way.”

While a declining global market for oil would give companies less cash flow to absorb cost overruns and operating losses in their CCS operations, Kalegha said there may still be uses for the technology. “CCS is not tied solely to the oil industry,” he wrote, “and could still play a role across other hard-to-abate sectors.”