Adding substance to Vietnam’s climate commitments 3 December 2021

In his speech at 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh announced that the country would aim for a net-zero emission target by 2050. With this move, Vietnam has joined the group of about 140 countries that pledged to net-zero emissions by the middle of the century.

Numerous challenges remain. Harmonising domestic economic development and global environmental commitments is not an easy task. In developing countries, the demand for increasing emissions along a traditional development trajectory is high and the resources to switch to a new greener pathway are often limited.

Vietnam’s CO2 emissions rose to 282 million tonnes in 2019, second only to Indonesia in Southeast Asia. Its total annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are projected to increase by 7 per cent this decade under the business-as-usual scenario. Per capita CO2 emissions rose to 2.9 tonnes in 2019, but remain lower than Thailand and Malaysia.

Fossil fuels are estimated to constitute about half of Vietnam’s electricity mix by 2030 as of October 2021. Before COP26, Vietnam’s effort was ranked highly insufficient to achieve the global emissions reduction target set in the Paris Agreement. Strong determination is needed for Vietnam to realise its net-zero emissions commitment, requiring radical changes in the country’s economic structure.

There will be both winners and losers in the energy transition, so quick consensus among stakeholders is unlikely. For example, the change would sensibly involve cancelling new coal power plants. While this move would create significant net social benefits — such as reducing local air pollution and avoiding deadlocks of not being able to secure financing sources — resistance from some stakeholders in the coal industry is foreseeable.

Vietnam has opportunities to pursue the net-zero emission target with domestic resources and international support, but a concrete and actionable plan is vital to guiding the process. Key elements of the plan include clear and ambitious targets, detailed responsibilities of stakeholders, and close monitoring mechanisms. Better communication about the potential benefits and support for the affected groups in the transition would facilitate adoption and implementation of the plan.

Plans to replace coal with imported liquefied natural gas for power generation need careful reconsideration. Natural gas is not a zero-carbon energy source. It will also take years to establish the infrastructure needed for new gas power plants. This poses a high risk of stranded assets, given the rapid decline in technology costs of the already cost-competitive zero-carbon energy sources of solar and wind.

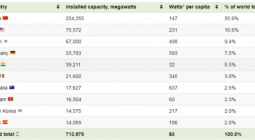

Increasing targets for solar and wind energy in the coming Power Development Plan 8 would boost their uptake. Vietnam has the potential to achieve over 90 per cent penetration of domestic solar and wind power, and off-river pumped hydro energy storage in its electricity mix at a competitive cost. The impetus for ramping up renewable energy uptake could be built on the country’s early success in solar and onshore wind power development that made it a leader in Southeast Asia.

Offshore wind power can contribute to GHG emission reduction. Vietnam has 475 gigawatts of offshore wind power technical potential within 200 kilometres of the coast, equal to about eight times Vietnam’s total installed power capacity as of 2020. The World Bank estimates that by replacing coal power with 25 gigawatts of offshore wind power by 2035, Vietnam could avoid over 200 million tons of CO2 emissions — nearly one third of the country’s energy sector emissions under the business-as-usual scenario.

Offshore wind power could be deployed at scale to meet domestic demand and for export to other countries. Other strategies include enhancing energy efficiency, upgrading transmission, investing in energy storage systems, and developing a competitive wholesale electricity market.

Decarbonisation in other sectors such as transport and industry is vital. Potential policies include incentivising electric vehicles, reforming subsidies for fossil fuels, and speeding up the implementation of carbon pricing. These would need to be reflected in the coming National Energy Development Strategy, in addition to the Power Development Plan 8.

Boosting efforts to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation would add substance to Vietnam’s commitment to net-zero emissions while mobilising international financing.

International support is crucial for Vietnam and other developing countries to unlock opportunities to pursue net-zero emissions targets. Greater technology transfer and financial assistance from developed to developing countries would speed up efforts to address global climate change. It would also operationalise the ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ principle adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The COP26 outcomes are expected to increase global assistance to developing countries. Opportunities exist for Vietnam to embark on a post-pandemic green recovery and enhance its contribution to global emissions reductions.

Thang Nam Do is a Research Fellow in the Zero-Carbon Energy for the Asia-Pacific Grand Challenge Program at the ANU Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions, The Australian National University.

Thang Nam Do, ANU