Australia's record spring heat one-in-500,000 without climate change: analysis.

This year’s spring temperatures would be ‘virtually impossible’ without human greenhouse emissions, according to new report.

Australia’s hottest spring on record, which saw temperatures more than 2C above average, would have been “virtually impossible” without human-caused climate change, new analysis has found.

A spring as hot as the one Australians just experienced would come along only once every half a million years without the extra greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, climate scientist Dr David Karoly told the Guardian.

Karoly warned that Australia was almost certain to experience even hotter temperatures and break further records over the coming decades.

The analysis, published by the National Environment Science program’s Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub, uses a method employed in previous peer-reviewed studies.

The Bureau of Meteorology announced earlier this month the spring of 2020 was the hottest since reliable records started in 1910, with Australia’s temperature 2.03C above the average taken from 1961 to 1990.

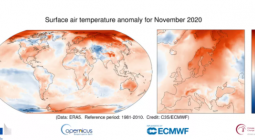

The final month of spring, November, was especially hot, with temperatures 2.47C above average.

The new analysis from Karoly used data produced from work led by climate scientist Dr Sophie Lewis, now the ACT’s sustainability and environment commissioner.

Using results from 11 different sets of climate models, the researchers ran the models with today’s levels of greenhouses gases. Those models were also run with the greenhouse gases generated by humans removed.

With elevated greenhouse gases, the models show a spring where the average temperatures exceed 1.8C comes along about once every eight years. Without the human influence, the 1.8C threshold is only broken once every 500 years.

The analysis says: “Both the observations and the climate model data show that the record 2020 spring temperature across Australia would have been virtually impossible without human-caused climate change.”

Karoly, the leader of the hub, said the results showed that the likelihood of having a spring as hot as the one Australians had just experienced without human-caused climate was one in 500,000 years.

He said: “This helps us to better quantify the contribution of climate change. It allows us to foreshadow even greater extremes and records becoming more common and larger.

“Climate change is already affecting the climate extremes like the bushfires on Fraser Island and the dry conditions in Queensland.”

He said Australia had already warmed by about 1.5C and that heating would continue in the coming decades.

“We are very likely to reach two degrees of global warming even if we rapidly reduce emissions.”

He said the unprecedented conditions that delivered the devastating bushfires of last summer would become much more common by 2050.

Dr Andrew King, a climate scientist at the University of Melbourne, specialises in analysing the human contribution to extreme events.

King, who was not involved in the analysis, said the approach was “robust” and if anything was probably conservative.

“In the last decade or so we have had big growth in this area of event attribution. This [analysis] uses a well-established method and it’s based on analysis from peer-reviewed studies.

King said those spring temperatures had come despite Australia being influenced by a La Nina climate system, which tends to lower temperatures.

“It is reasonable to say it is virtually impossible to get these (spring) temperatures without climate change.”

The analysis is part of a fast-developing field of research known as climate attribution, where scientists analyse the effect of increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere on extreme weather events such as flooding, temperature extremes, marine heatwaves and bushfires.

The Bureau of Meteorology has also developed a method, published in a journal in November, that calculates the human contribution to heat extremes before they happen by adapting the models used for seasonal forecasts.

That method was used retrospectively to discover half the extra heat in the hottest October on record – in 2015 – was due to extra greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

9 December 2020

The Guardian