Global rich must cut their carbon footprint 97% to stave off climate change, UN says.

This year's economic shutdowns have done little to reduce the world's carbon emissions. While pollution has dipped, greenhouse gases keep accumulating in the atmosphere, locking in future decades of climate disruption and extreme weather. A recent United Nations report says the so-called emissions gap — the "difference between where we are likely to be and where we need to be" on climate policy — is as big as ever.

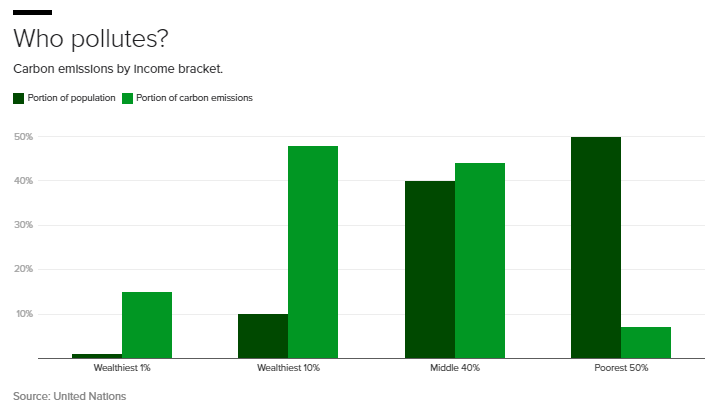

As for who's chiefly responsible for the gap, it's the global rich, the report says. Just 10% of the world's population emits nearly half of the world's carbon pollution. The top 1% of income earners around the world, a group that includes 70 million people, account for 15% of emissions — more than the 3.5 billion people in the bottom 50%.

The upshot: When it comes to cutting their emissions, "The richest 1% would need to reduce their current emissions by at least a factor of 30, while per capita emissions of the poorest 50% could increase by around three times their current levels on average," the U.N. says. That translates into a reduction of 97% in carbon emissions for the wealthiest people.

More money, more pollution

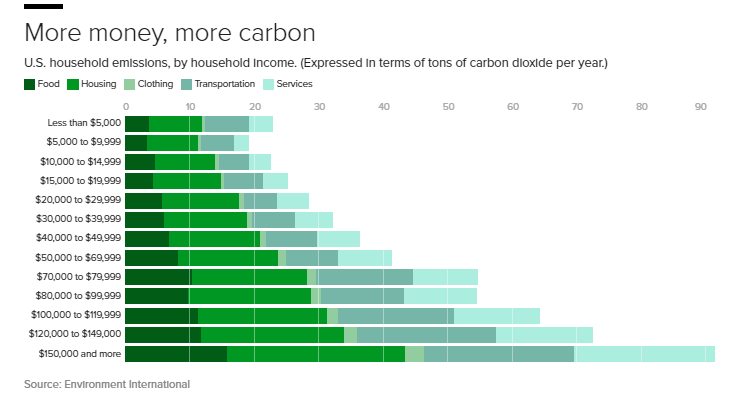

Researchers have long known that carbon emissions are closely tied to income. "Higher income per capita means higher emissions per capita, most of the time," said Justin Caron, an environmental economist and professor at HEC Montreal, the University of Montreal's business school.

"It's not true of other pollutants," he added. "Rich countries tend to be cleaner on other things, have cleaner water and air, but that's not true for CO2."

That's partly because wealthier people consume more: They buy more goods, own more cars, have larger houses that take more energy to heat and cool. Carbon emissions are effectively embedded across much of the global economy, so consuming in general is akin to polluting.

But some particularly polluting activities remain the province of the global rich. At the top of the list: international air travel, which, if it were a country, would be the eighth-largest emitter in the world.

While flying has become more democratized in recent years, "Aviation remains the preserve of high-income earners," the UN said. A study last month in the journal Global Environmental Change found that just 2% to 4% of the world's inhabitants boarded an international flight in 2018, and half of all emissions from commercial flights come from 1% of the world's population. (That's not accounting for private flights, which are even more intensely polluting.)

"Per capita emissions are one more manifestation of the tremendous inequality that's a fact of life in our society that we need to address," said Taryn Fransen, a senior fellow with the Global Climate Program at the World Resources Institute.

Galloping inequality

Inequality is also a fact of life within the wealthiest countries that pollute the most. (Nearly 80% of global emissions came from the member states of the G20, the UN said.) For instance, a household in the U.S. that makes more than $150,000 has a carbon footprint four times the size of a household that makes just $9,000.

If there is a silver lining in these figures, it may be the possibility of tackling both climate disruption and economic inequality in one fell swoop.

Economists' favorite tool for this is a carbon tax, which would make the most polluting activities (such as flying) much more expensive and thereby less popular. Leading inequality scholar Thomas Piketty has proposed solutions like taxing airplane tickets or creating a global fund for climate restoration projects, with the biggest polluters contributing most.

The U.N. report focuses on the importance of lifestyle change: Choosing less polluting forms of transportation, like bikes, trains and buses, and moving to plant-based diets. However, it's unlikely that large numbers of people will voluntarily shift their consumption patterns without help from the governments and corporations that encouraged those patterns in the first place.

"People are not driving a car because they want a carbon-intensive lifestyle — people are driving a car because that is the access to transportation that our society provides," Fransen said. "It's the responsibility of policymakers to support alternatives that give people the goods they need without destroying the climate."

Policymakers have not done so, historically, because the wealthy people who do most of the polluting also have the greatest ability to shape economic and environmental policies. This year's economic crash could help jump-start climate measures by spurring environmentally beneficial investment — for instance, funding a large expansion of public transit, which has taken an unprecedented hit thanks to COVID-19, or adding bike infrastructure. Lawmakers could also make financial relief for polluting industries conditional on meeting environmental goals.

Too few countries have done so, the U.N. says, instead choosing to double down on polluting industries. For instance, while the drop in air travel during the pandemic can be seen as a positive development for the planet, the U.S. and most European Union countries bailed out airlines with no environmental requirements, although the U.S. deal included temporary worker protections.

Changing social norms could also play a part, albeit a small one. If, post-pandemic, large numbers of people continue to work from home and conduct business on Zoom, rather than flying, it could make an impact.

"At some point, air travel is the most CO2-intensive activity that we do," Caron said. "Any dent into that could have a long-lasting positive effect."

*Watch the videos here

16 December 2020

cbs news