How to Sell ‘Carbon Neutral’ Fossil Fuel That Doesn’t Exist

The junior trader at TotalEnergies SE was essentially winging it by orchestrating the French energy giant’s first shipment of “carbon-neutral” natural gas last September. It’s the greenest-possible designation for fossil fuels and an important step toward making the company’s core product more palatable in a warming world. Failing the deal involved googling and guessing. Hear this story.

According to people with knowledge of the deal, who asked not to discuss the private transaction, Total had proposed the business after learning Total had already purchased two carbon-neutral cargos from rivals in Royal Dutch Shell plc. . It was only after the inexperienced team went ahead to figure out how to neutralize the emissions contained in a Hawking tanker filled with liquefied natural gas, one of these insiders said. His first step was to search the Internet for worthy environmental projects that could make up for the pollution.

Thousands of miles away, a volunteer from Zimbabwe named Kembo Magonio will spend the spring months clearing stubborn jumbles of branches near the densely forested border with Mozambique. Forest fires leap between the two countries, ruining trees before anyone can answer. “This whole bush can be torn to the ground if we don’t do what we’re doing,” Magnio says, hacking away with his weapon. Their work is conducted by a group partially funded by Total’s carbon-neutral deal.

In the complex new math of climate solutions, brush-clearing villagers in southern Africa could redefine the network of billion-dollar global commerce. Environmental projects stand as shadow partners to far-reaching emissions-heavy energy trades.

What Total’s gas cargo puts into the atmosphere, the villagers carrying weapons will remove it. That’s the principle.

But for this to work, Total’s pioneers of carbon neutrality first needed to find green projects capable of meeting two requirements: generating carbon credits backed by an international organization, without costing too much. After struggling to come up with an answer, the team set up a meeting with South Pole, a project developer based in Zurich who came recommended by rival traders. Thus the $17 million LNG transaction ended $600,000, in part, to pay for forest conservation in Zimbabwe.

The resulting trade looks like a win-win for all. Total kept its promise to investors to reduce its carbon footprint. Poor communities received financial assistance. And the buyer, China National Offshore Oil Corp, cited the shipment as one of the steps it has taken to “provide green, clean energy to the nation.” But climate experts and even a key organizer behind the deal say it will do almost nothing to reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, falling far short of neutral.

“The claim that you can sell fossil fuels as carbon neutral because a few dollars you put into tropical conservation is a hedge,” says Danny Cullenward, a Stanford University lecturer and policy director at CarbonPlan, a non-profit group. Not a valid claim.” Which analyzes climate solutions for impact.

At best, Cullenward says, efforts to stop deforestation by stopping forest fires can only avoid the additional heat-trapping gas released when trees are burned. Rural villagers can do little to combat the widespread pollution caused by natural gas, other than making energy traders and consumers feel good about supporting green causes in areas where money is scarce.

Total said in a statement that it does due diligence on the offset projects and confirmed that it has split the cost of the offset in the LNG transaction with Cnooc. The French company declined to discuss details, including the prices it paid for the carbon credits, citing a non-disclosure agreement. Cnooc did not respond to requests seeking comment. Total also said it does not count carbon credits in its company’s emissions reports or as part of its plan to reach net zero by 2050. “An important tool,” the company said, “offsetting cannot be considered as a substitute for direct emissions reductions by corporates, but as a supplement.”

The use of scientifically defined terms such as “carbon neutral” and “net zero” in marketing parlance creates additional confusion. Both terms mean balancing any emissions added to the atmosphere with an equal amount of removal. Most experts agree that avoiding deforestation is not the same as removing greenhouse gases. “This paradigm,” warns Clanward, “is encouraging an imaginary engine that does not help us advance our net-zero goals.”

That approach is not reserved for outside critics. The leader of the South Pole, which helped develop the Zimbabwe project and sold its carbon credits to Total, believes forest conservation cannot fix pollution from natural gas. “It’s so obvious bullshit,” says South Pole co-founder Renat Heuberger. “Even my 9-year-old daughter will understand that this is not the case. You’re burning fossil fuels and creating CO₂ emissions.”

Total’s product began to warm the planet at the moment of its extraction from the deep-sea ichthys region off the Australian coast. Every part of its lifecycle generates a greenhouse gas. Sending gas to an export facility via an 890-kilometre (553-mile) pipeline runs the risk of leaking methane, a potent pollutant that traps 80 times more heat than CO₂ in its first two decades. Cooling the gas into a liquid for shipping results in additional emissions. Even a tanker bringing LNG to Shenzhen in southern China burned some fuel while sailing.

At the final destination, after Cnooc claimed the cargo last September, the LNG was burned to power the city’s countless factories or power grids serving more than 12 million people. This would leave a centuries-old remnant of atmospheric CO₂ that Total’s traders had to neutralize. but how much? Total and Cnooc agreed to set the shipment’s emissions at 240,000 metric tons of CO₂, the same amount of pollution generated by 30,000 American homes a year.

This figure is, at best, a rough estimate because there are too many variables. “No one has made the exact calculations,” says Fauzia Marzuki, an analyst with the research group BloombergNEF. “All these deals are making assumptions.”

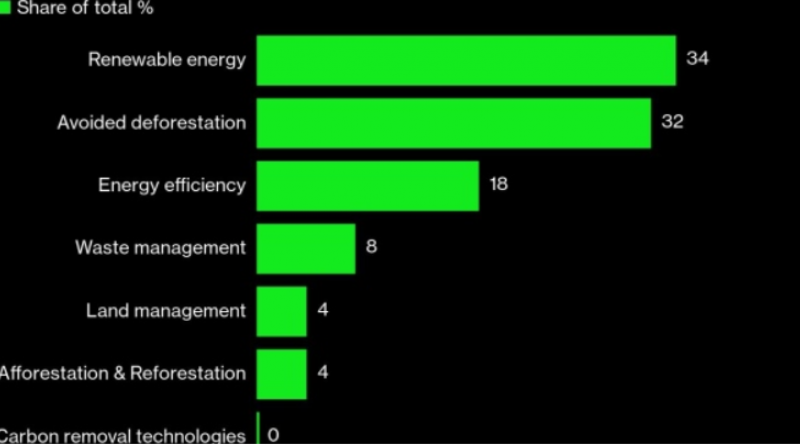

If Total’s team started out as rookies in carbon math, then South Pole experts arrived as old hands. The company has been generating credits for more than 15 years – long before the corporate world took an interest in their emissions-reducing power – and today operates in dozens of countries. In virtual meetings, South Pole sales representatives set out options, according to people familiar with the transaction. They had the cheapest offsets to support renewable energy projects, while the most expensive funds to plant new trees helped with deforestation efforts.

According to the New York-based think tank Eurasia Group, the cost of sufficient carbon credits to offset shipments of LNG could be anywhere between $1 million and $15 million. Most trades fall on the lower end of the spectrum in terms of cost and quality. Traders in Asia participating in similar deals say the offsets involved typically sell for less than $6 a tonne of CO₂.

“We’re hearing low single digits,” says Lucy Cullen, an analyst at energy consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd., “what companies pay per ton.” “It makes sense from a commercial standpoint.” By comparison, Bill Gates said in an interview earlier this year that he would pay about $600 a ton to suck up carbon from the air using state-of-the-art technologies as a way to offset his personal carbon footprint. We do.

Total decided to take the bulk of its offset from the Hebei Guiyuan wind farm project, located in a Chinese steel-making province surrounding Beijing. A similar argument linked wind farm and wildfire prevention in Zimbabwe. In this case the electricity generated by wind turbines would theoretically avoid the use of Hebei’s dirty coal-fired power plants. The resulting reduction in emissions compared to an alternative scenario in which only coal power was used would form the basis for neutralizing Total’s gas deal.

Total opted to add additional credits to the project in Zimbabwe’s Kariba region, which South Pole co-developed with Carbon Green Africa. Those credits cost more than a Chinese wind farm, but average less than $3 per ton, according to people familiar with the deal. Total declined to comment, citing a non-disclosure agreement.

Did the deal money help reduce emissions in China? The Hebei wind farm has been generating clean energy for more than a decade, and it’s unlikely it will stop doing so without several hundred thousand dollars from Total and Kanok, says Gilles Dufrasne, policy officer at the nonprofit Carbon Market Watch. will do it.

Vera, the organization that certifies the Hebei credits used in the total deal, has updated its policies to largely exclude grid-connected renewable energy. If wind farm operators tried to register as an offset project today, “it would not be accepted,” Dufrasne says.

When climate scientists think of offsets, the key concept they grapple with is called “excession.” You only balance the carbon scale if you actually remove CO₂ that would not have been absorbed without your support. This is a very tricky concept that can be misused. After all, how do you prove that something bad would have happened if you weren’t…

August 2021

Bloomberg Green