Op - The Guardian view on the Cop26 agreement: unfinished business

The best thing about the Glasgow agreement is the chance it offers for tougher emissions cuts next year.

The anti-global heating movement is not strong enough. With last year’s defeat of Donald Trump, its enemies lost their most powerful figurehead. But the governments of Australia, Brazil, Russia and Saudi Arabia continue to obstruct progress and at Cop26, yet again, they and the other backers of the fossil fuel-powered status quo outgunned supporters of the immediate decarbonisation that is needed, if the goal of limiting temperature rises to 1.5C is to stay within reach. Now the Glasgow conference is over, the most important question for all those seeking to avoid and reduce climate harms is how to speed up the transition.

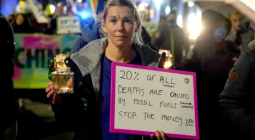

Ramping up the pressure on polluters – both nations and companies – is the obvious answer. Questions surrounding tactics remain fraught, as the recent debate over protests by Insulate Britain illustrates. But there is no question that civil society has a vital role to play. If people, in a few years’ time, are to look back on Cop26 as a success, it will be because the Glasgow agreement created the mechanism whereby countries must revisit their emissions-cutting pledges every year, and the political conditions changed sufficiently to ensure that existing promises were strengthened.

If Glasgow goes down in history as a failure, it will be because emissions keep on rising. This would mean that the world’s richest countries and organisations make the choice described in the opening speech by Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, as “the path of greed and selfishness”. That is, the choice not to protect the world’s poorest people and places from catastrophic climate harms – including sea level rises that are already engulfing small-island states, humanitarian disasters caused by extreme weather events, and temperatures that will make large areas of the planet uninhabitable.

That India and China are both actively engaged in the Cop process, alongside Joe Biden’s White House, is heartening, despite Xi Jinping’s absence. The new commitment to joint working by China and the US, and deal struck on methane, are tangible advances. But India’s last-minute insistence that a reference to “phasing out” coal be changed to “phasing down” was disappointing. India’s per capita emissions are around a 10th of the US’s, and a third of the UK’s. Environmental injustice largely fits an existing template of unequal wealth distribution, with the countries that have benefited least from fossil fuel-powered growth suffering the worst consequences. But the shocking failures of western governments with regard to polluting industries and subsidies – plans for a new coal mine in Cumbria are a particularly egregious example – in no way excuse the pro-coal policies pursued by India, China and others. Scientists are unequivocal that this dirtiest of fuels must be eliminated, and rapid falls in the price of renewables mean that cost is no excuse.

Emissions must shrink by around 45% this decade to keep alive the chance of limiting heating to 1.5C. Based on current commitments, we are on track for 2.4C. Next year, at Cop27 in Egypt, governments have another chance. If they are to take it, the pressure on them, and on the central banks and private financial institutions – that should long ago have grasped their responsibility to shut down the environment-wrecking fossil fuel industries, instead of propping them up – must be massively stepped up. Needless to say, there is no time to waste – a fact clearly understood by Cop26 president, Alok Sharma, who was visibly upset when he told delegates on Saturday that he was sorry for the agreement’s limitations.

14 November 2021

The Guardian