Biden’s climate change plans can quickly raise the bar, but can they be transformative?

The day Joe Biden becomes president, he can start taking actions that can help slow climate change. The question is whether he can match the magnitude of the challenge.

If his administration focuses only on what is politically possible and fails to build a coordinated response that also addresses the social and economic ramifications of both climate change and the U.S. policy response, it is unlikely to succeed.

I have spent much of my career working on responses to climate change internationally and in Washington. I have seen the quiet efforts across political parties, even when the rhetoric was heated. There is room for effective climate actions, particularly as heat waves, wildfires and extreme weather make the risks of global warming tangible and the costs of renewable energy fall. A coordinated strategy will be crucial to go beyond symbolic actions and bring about transformative change.

Starting on day one

Let’s first take a look at what Biden can do quickly, without having to rely on what’s likely to be a divided Congress.

Biden has already pledged to rejoin the Paris climate agreement. With an executive order and some wrangling with the United Nations, that will happen fairly quickly. But the agreement is only a promise by nations worldwide to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change.

To start moving the country back toward its obligations under the Paris Agreement, Biden can recertify the waiver that allows California to implement its fuel economy and zero-emissions vehicle standards. The Trump administration had revoked it. California is a big state, and its actions are followed by others, which puts pressure on the auto industry to meet higher standards nationwide.

In a similar way, Biden can direct government agencies to power their buildings and vehicles with renewable energy.

The administration can also limit climate-warming greenhouse emissions by regulating activities like the flaring of methane on public lands. The Trump administration rolled back a large number of climate and environmental regulations over the past four years.

There are even legislative actions that could get through a divided Congress, such as funding for clean energy technology.

The big job: Transformational change

That’s the easy part. The hard part is catalyzing the transformational changes needed to slow global warming and protect the climate our economy was built on.

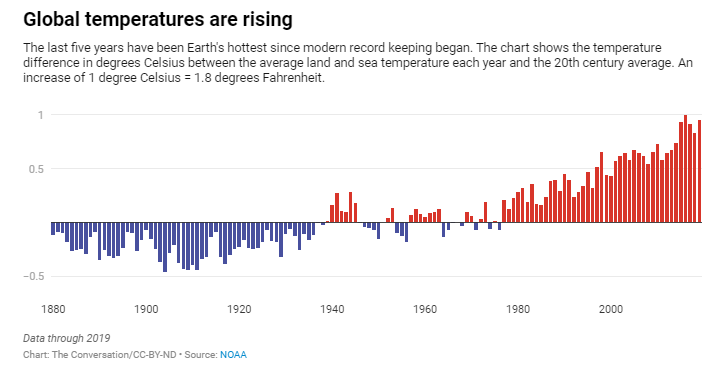

The last five years have been the hottest on record, and 2020 is on pace to join them. Meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals for keeping global warming in check will require reworking how we generate and transmit energy and overhauling how we grow food in ways that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Biden has pledged to lay the groundwork for 100% clean energy by 2050, including investing hundreds of billions of dollars in technologies and industries that can lower emissions and create jobs. His ideas for transforming food systems have been less concrete.

The new administration will have to walk a tightrope. It can’t risk spending down its political capital on actions that are possible but don’t amount to much. It also has to recognize the risk of public backlash to anything that might raise costs, be labeled “socialism” by opponents or leave part of the country harmed.

Transformative solutions will have to address both the benefits and the costs, and provide a path to a healthy future for those facing the greatest losses. That means, for example, not just ending coal burning, a significant contributor to climate change, but also helping communities and workers transition from coal mining to new jobs and economic drivers that are healthier for the environment.

What needs to happen first

One of the big challenges – and the place where Biden needs to start – is the lack of understanding of systemic risks, opportunities and costs of both climate actions and inaction.

Right now, there is no federal agency tasked with developing a systemic understanding of climate change impacts across society.

An existing executive branch entity, such as the Council on Environmental Quality or the U.S. Global Change Research Program, could convene a task force of political staff, academics and civil society to assess climate policy proposals, identify the benefits and costs and then advise the administration. Working across agencies, the task force would be positioned to look at the entire system and identify the wider effects of proposed policies or actions and how they might interact. Similar entities, such as the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and Congressional Research Service, are already central to policymaking.

Their work will have to move fast. The very nature of complex systems means the task force will provide advice on climate actions under uncertainty.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Aligning the possible and the transformational is the challenging work of politics, and this is where Biden’s 47 years in Washington and reputation for working across the aisle are invaluable.

It will be extraordinarily challenging work to match an extraordinary challenge. It is also necessary if the Biden administration, headed by a man who called himself a transition candidate, wants to leave his country and the world better than they found it.

10 November 2020

THE CONVERSATION