Opinion: Keeping fossil fuels in the ground is the only corporate strategy possible.

The net-zero road map published this week by the International Energy Agency shows a way forward to a new, cleaner world in line with the Paris Agreement, but the task ahead is massive and companies need to make radical change today.

The net-zero report published by the International Energy Agency (IEA) this week is groundbreaking and we should celebrate the overall direction of its vision. However, amid the (virtual) backslapping and handshaking, the enormity of the task ahead must not be downplayed.

The first published energy scenario to explicitly meet the aim of the Paris Agreement to keep global warming below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the report has sent shockwaves around the world. Environmentalists have been calling for years for fossil fuels to be kept in the ground if dangerous levels of climate change are to be avoided. The IEA stopped short of using this phrase, but the point has been made. Fossil fuels are largely incompatible with a net-zero emissions world.

No new oil and natural gas fields, no further investment in new fossil fuel supply projects, by 2035 no sales of new internal combustion engine passenger cars – the drum beat was loud and clear. In a follow-up interview, Fatih Birol, the agency’s executive director, even went as far as to say that putting money into oil and gas projects could now be considered a “junk investment”.

All this from the body that, until very recently, was considered a conservative voice, too tied to its oil-industry roots to be considered an ambitious voice in the climate space.

However, if fossil fuels are to fall from almost four-fifths of total energy supply to slightly over one-fifth by mid-century and the global electricity sector is to reach net-zero emissions by 2040, business-as-usual has to end today.

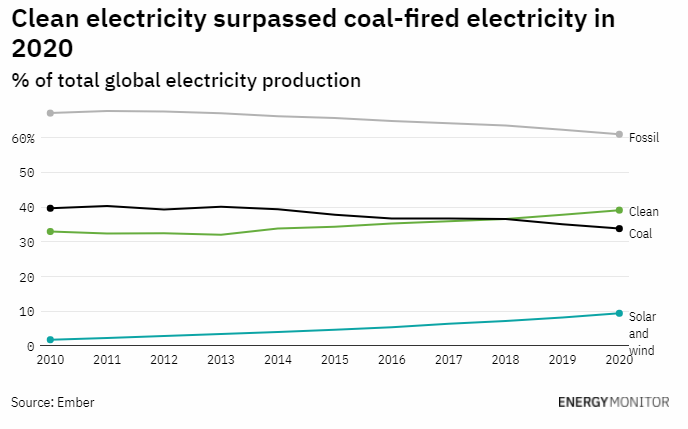

There is plenty of change to celebrate with record amounts of renewables in the world’s energy mix and other climate-positive firsts, but there is also, unfortunately, a plethora of data showing that in the grand scale of things, we are doing little more than fiddling while Rome burns.

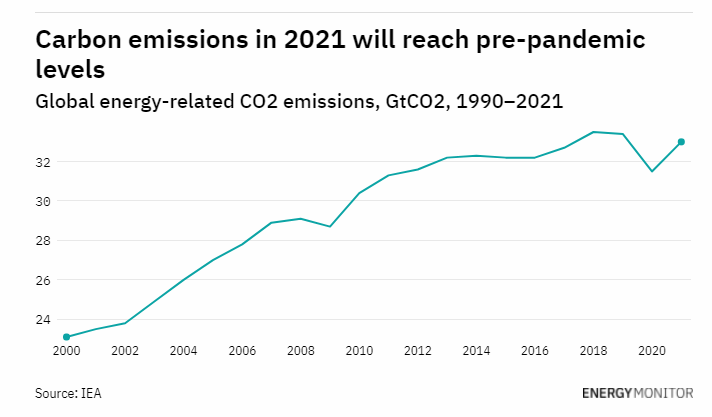

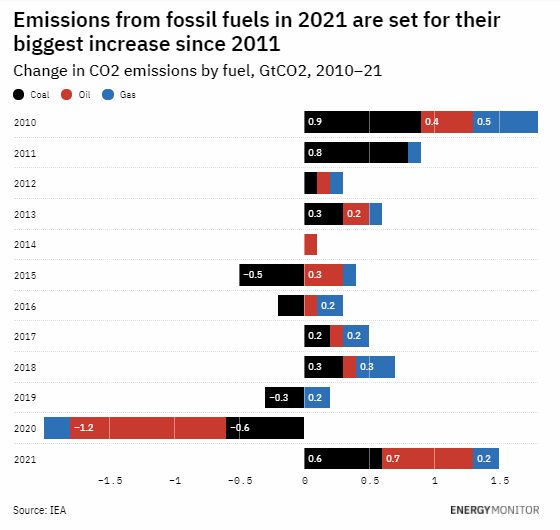

Despite pledges by governments the world over to “build back better” after the Covid-19 pandemic, fossil fuel emissions are set for their biggest increase since 2011 this year and will reach pre-pandemic levels.

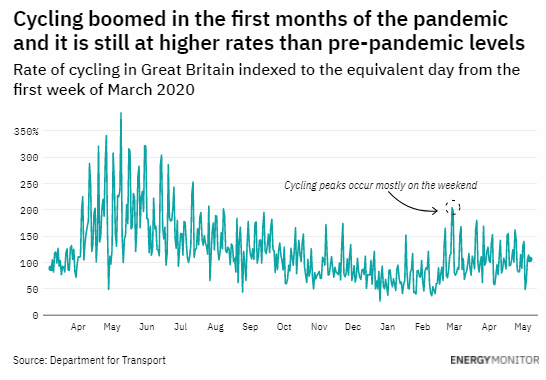

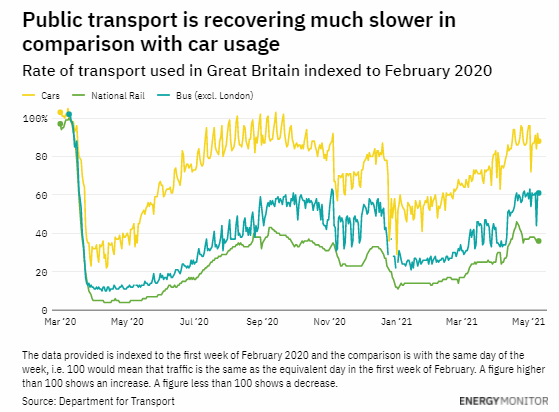

Living in Brussels, Belgium, anecdotal evidence suggests people’s love affairs with their cars have not diminished during lockdown, even if bike infrastructure is increasing in cities everywhere. Data from the UK Department for Transport seems to bear out this assumption. Cycling boomed in the UK in the first months of the pandemic and remains at a higher rate, but peaks in use tend to be at the weekend, suggesting cycling still remains a pleasurable pastime and does not yet have wide commuter cache.

While pre-Covid levels of public transport users are yet to bounce back, people are quickly returning to their cars. Road transport is responsible for around a fifth of the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

The switch to electric vehicles will help turn this around, but EVs are only as green as the energy source that powers them. If our energy world is to look “completely different” by 2050 as the IEA suggests, investors and fossil fuel companies must unreservedly embrace this new world. Oil majors are investing in clean energy and many, such as BP and Shell, have published net-zero plans. However, none have committed to fully ending their love affair with fossil fuels, in particular with natural gas.

Research by UK think tank Carbon Tracker found that in 2020 all major oil companies sanctioned projects that fall outside the goals of the climate agreement and will fail to deliver adequate returns in a low-carbon world.

Silver bullets and unicorns

“We cannot have major energy companies out of sync with scientific thinking,” says Gail Whiteman, sustainability professor at the University of Exeter Business School. Shell’s energy transition plan relies “unrealistically on negative emissions technologies and massive, and wholly unrealistic, offsets through tree planting which requires a new forest the size of Brazil,” she says. Carbon capture and storage is a key tenet of the company’s vision.

“Shell is relying on silver bullets,” Whiteman says. “This kind of disconnect is confusing and downright dangerous. For the IEA pathway to have value, the world will need to stop believing in unicorns and listen and act upon the science.”

Looking at the experiences of other sectors, such as the telecoms industry, that have been forced to reform, “it is possible but really hard”, says Kingsmill Bond, energy strategist at Carbon Tracker. “It takes proper commitment to change”, something he believes is still lacking from fossil fuel companies. “The majors thought they could greenwash and this problem would go away,” he says. Now they must “stop fiddling and get on with it”.

For Bond, “new business models” are key to this transformation, suggesting fossil fuel companies can either “run down and become cash cows for stakeholders or reinvent themselves”.

Whiteman cites DSM, the global science company that now specialises in nutrition and health products, but was initially established as the Dutch State Mines company to mine coal, as an example of transformation. Such significant change requires “leadership and companies to make decisions based on science; we need all hands on deck,” she says.

Schneider Electric has made a similar journey, first from mining company to provider of 20th-century electrical solutions and then, most recently, to a company leading the ‘smart’ clean energy transition with efficiency, sustainability and digitalisation at its core.

Danish power

Power giant Ørsted, headquartered in Denmark, has also successfully gone through the transformation from fossil fuels to green energy.

“All businesses and cases are different, and so it is difficult to speak for other companies,” says Ørsted’s Jakob Ask Bøss. “However, based on our learnings, what often seems to be a technological or financial challenge is in essence a leadership challenge. You can achieve much more than you originally imagine. The world needs companies to seek the opportunities of the green transformation even if this involves a leap of faith.”

The IEA’s narrative is one of urgency, but of positive gain too. Its net-zero road map will bring “a historic surge in clean energy investment that creates millions of new jobs and lifts global economic growth,” said Birol.

Dave Jones, analyst at UK think tank Ember, believes the IEA report and its framing will make it much more difficult for companies not to follow Ørsted’s lead. “People power is really important; the report will increase pressure from different stakeholders, including civil society, for change,” he says.

We must hope this is the case and that all companies are listening and acting. Many would argue that nearly 89% of Shell’s shareholders failed this week to exert the necessary pressure by backing the company’s energy transition plan. As the IEA was calling time on new oil and natural gas fields, Shell was receiving backing to continue to explore in new regions for oil and gas until 2025.

“Our road map shows the priority actions that are needed today to ensure the opportunity of net-zero emissions by 2050 – narrow but still achievable – is not lost,” said Birol. Every step in the wrong direction narrows this window even further.

May 2021

ENERGY MONITOR