China's surprise climate pledge leaves Australia 'naked in the wind', analysts say.

Beijing now has a more ambitious long-term climate goal than Australia – and there are fears that could have a dire impact on our economy.

Australia’s resistance to a mid-century net zero emissions target is likely to become increasingly unsustainable after China surprised global leaders by pledging it would reach “carbon neutrality” before 2060, climate analysts and advocates say.

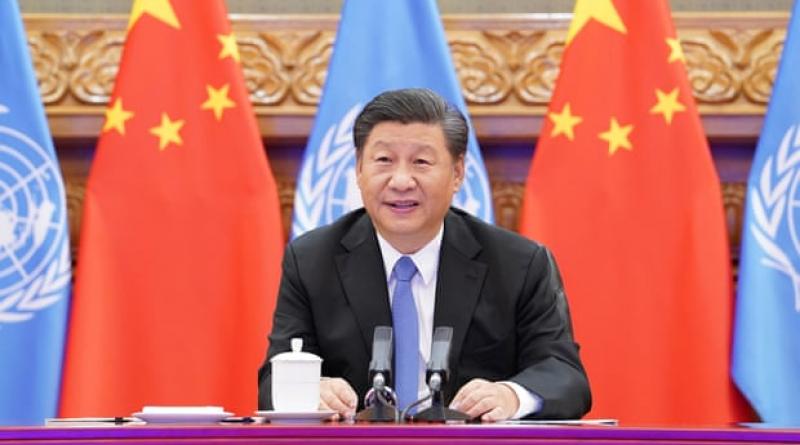

The announcement by the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, at the UN general assembly on Tuesday means the world’s biggest emitter has a more ambitious long-term climate goal than Australia despite still being considered an emerging economy.

Xi said China would update its Paris agreement commitments to carbon dioxide emissions peaking before 2030 and reaching “neutrality” – zero additional emissions into the atmosphere – by 2060. He called for a “green recovery of the world” from the Covid-19 pandemic and promised to introduce “vigorous policies”.

It is the first time China, which is responsible for about half of global coal use and has driven much of the recent rise in emissions, has said it would end its net contribution to the climate crisis. It follows the European Union last weekstrengthening its Paris commitments, including pledging to cut emissions by 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels.

The Australian prime minister, Scott Morrison, said on Sunday the government had committed to reach net zero emissions in the second half of the century, rejecting a call from business, industrial, farming and union groups for it to set that target for 2050. The government has not set a formal long-term target, and has said it does not intend to change its 2030 goal – a 26-28% cut below 2005 levels – before a major UN climate meeting in Glasgow next year.

Dean Bialek, a former Australian diplomat to the UN now working with ex-UN climate chief Christiana Figueres and the British government’s climate action champion Nigel Topping, said China’s increased climate ambition was “a very important step forward” and would shift the focus of global climate talks.

He contrasted it with the Australian government releasing a low-emissions technology statement on Tuesday that was “completely open ended” on where the country’s emissions were headed.

“We often hear from the Australian government that China’s doing nothing and that as a result it’s useless for Australia to propose ambitious targets, but this new announcement flies in the face of that,” Bialek said. “It will further isolate Australia on climate policy internationally.”

He said Australia could end up exposed to measures that imposed a cost on the trade of carbon-intensive goods. “This is not just a moral multilateral argument. Australia’s laggard status might have very significant negative economic consequences,” he said.

Kobad Bhavnagri, the Sydney-based global head of industrial decarbonisation with analysts Bloomberg New Energy Finance, said China’s announcement was a monumental shift, noting the country’s per capita wealth remained a fraction of Australia’s.

“It basically leaves Australia naked in the wind,” he said. “The old excuses for our inaction are shattered. It is an unsustainable position for Australia to continue.”

Erwin Jackson, policy director with the Investor Group on Climate Change, said China’s announcement was a reminder that Australia, as a carbon-intensive economy, was heavily exposed to “the inevitable transition” to net zero emissions. “Unless Australia positions itself to attract investment in this transition it risks being caught up in a flight of global capital away from fossil fuels,” he said.

China’s previous commitment was to aim for its emissions to peak in about 2030. It follows a period in which the country has noticeably increased the construction of coal-fired power plants, leaving it with an oversupply.

China’s intentions on climate are often opaque, but there have been some recent signs it is re-thinking its stance. National oil company PetroChina announced a “near-zero” emissions target for 2050, and the People’s Bank of China has begun talking of the need for a “green” financial system in the wake of the pandemic.

Climate policy experts said Xi’s speech left several questions unanswered, including how “carbon neutrality” would be defined and whether the commitment applied to just carbon dioxide or all greenhouses gas.

More than 100 countries have net zero goals, but several larger countries have resisted, and global emissions reached a record high last year, largely due to rising Chinese CO2. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found global emissions would need to be about 45% below 2010 levels by 2030 and net zero by mid-century to limit global heating to about 1.5C, a goal that countries agreed in Paris they would pursue.

Momentum for further action will in part depend on the US presidential election. Bialek said Australia could be further isolated if Democratic candidate Joe Biden won in November. While Donald Trump is withdrawing the country from the Paris agreement, Biden has promised to re-join and take a global leadership role in tackling the issue.

A spokesperson for Angus Taylor, the minister for energy and emissions reduction, told Guardian Australia: “Australia’s emissions peaked more than a decade ago … Australia’s ambition is to be a global leader in technologies that will reduce emissions, lower costs and create jobs.”

The opposition did not respond to a request for comment before publication.

The Greens leader, Adam Bandt, said it would put pressure on Australia to announce a time frame for “complete decarbonisation” and meaningful shorter-term milestones. “Others are lifting their 2030 game and it’s about time Liberal and Labor did here too, because without strong action this decade we won’t keep global warming well below 2C.”

24 September 2020

The Guardian