Carbon Markets May Soon Free Billions for Investment. But Where?

New maps and analyses of carbon-rich regions could direct post-Glasgow funds where they’ll do the most good.

Nations clinched the Paris Agreement six years ago but finished writing it only at COP26 in Glasgow this month. There, negotiators finally checked the box on something called “Article 6,” a section of the 2015 climate pact governing how countries can trade credits to emit CO₂. The new standards should also impose structure and transparency on opaque voluntary markets where companies buy and sell carbon offsets.

This diplomatic breakthrough may build the confidence needed for billions of investment dollars to flow to recovery and conservation work, particularly in developing nations. But where should the money go? Demand is already high for projects that protect or restore land, generating offsets in the process. Credits that represent actual reductions in atmospheric CO₂ can’t come online fast enough — at least according to countries and companies hoping to buy their way, even partly, out of carbon debt. Use of offsets is dogged by an integrity problem and charges of greenwashing, ineffectiveness and local conflict.

Two recently released analyses suggest there is no shortage of help to protect land, regardless of whether help is direct government action, multinational funding or trustworthy carbon markets. The studies offer a useful way to think about the vast new world of what policy experts call “nature-based solutions.”

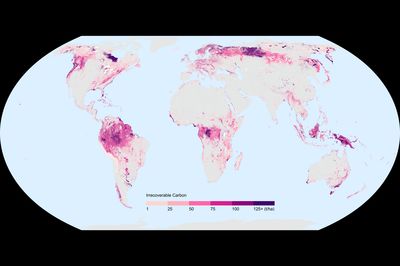

The first study offers a rigorously constructed map of the world’s most carbon-rich ecosystems, published in the journal Nature Sustainability. University and nonprofit researchers, led by the group Conservation International, have identified the places we absolutely can’t lose. Inspired by efforts to brand fossil-fuel reserves as “unburnable carbon,” the researchers define “irrecoverable carbon” as the forests, mangrove stands, peatlands and other areas that wouldn’t recover by 2050 if we wreck them. Half the world’s irrecoverable carbon is concentrated on 3.3% of the land, areas that together are equivalent in size to India and Mexico combined. It’s disappearing bit by bit every year, and holds 15 times the amount of CO₂ released in 2020.

The good news: New protections for 5.4% of this land would keep 75% of this carbon out of the atmosphere.

Source: Nature Sustainability; Conservation International

The map of high-carbon areas could be a useful resource for groups from biodiversity-focused activists to multilateral institutions like the World Bank. Companies that source raw material from forests should find it useful, the authors write, as they try to identify where they can stop underwriting destruction.

Well-constructed carbon markets can slow deforestation, channeling investment into areas where cutting trees has been the only development option. Allie Goldstein, Conservation International’s director for climate protection and a lead author, likened such investments to triage in a hospital emergency room that stabilizes the patient: Other programs can provide longer-term ecosystem care. “The map can give companies a clear vision where they should be investing,” she said.

There is a world of ecosystems in need of investments and ideas, such as the African Great Green Wall, a 5,000-mile band through the Sahel, from Senegal and Mauritania east to Ethiopia. The effort was begun in 2007 with the goal of restoring 100 million hectares (247 million acres) of land; so far, the initiative has completed just 4% of that total, according to a separate study in the same journal. Degraded land costs the region about $3 billion a year.

The authors tallied the value of goods produced in the region, such as crops and firewood, and of existing estimates of nonmarket benefits that ecosystems provide, like cleaning the air and water. They found that every dollar invested in restoration yields on average $1.20 in benefits. It’s not easy, though. Carbon markets in particular require stability and visibility uncommon in places where land ownership can change hands quickly and violence can disrupt life. Of the 28 million hectares accessible to Great Green Wall projects, half could be rendered inaccessible by violent conflict.

To date, carbon trading has not played a role in Great Green Wall projects, said Alisher Mirzabaev, lead author and senior researcher at the University of Bonn’s Center for Development Research. Funding to restore land has come from national budgets or international donors. The World Bank, France and the United Nations this year announced a $14 billion initiative to regreen the region.

“This paper, we hope, will be helpful in terms of targeting where to channel those investments,” Mirzabaev said. “We would like to guide those investments to the most efficient use.”

Eric Roston writes the Climate Report newsletter about the impact of global warming.

22 November 2021

Bloomberg Green