China losing interest in Australian coal isn't about diplomacy – it's simply market dynamics.

We need to discuss how communities and workers in the coal sector will cope with China’s push for self-sufficiency.

Australian politicians have been selling the “dream” of coal for years, but it’s a dream that is about to be mugged by reality.

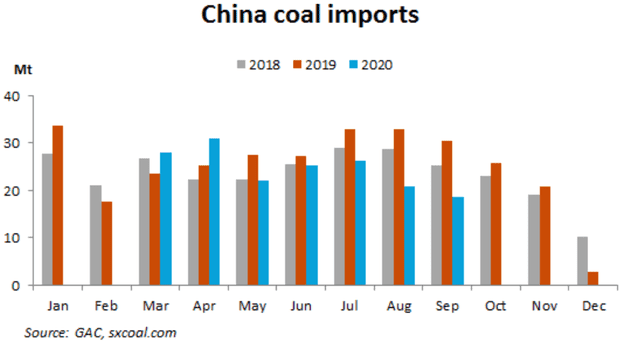

China’s coal imports have been weak all year. Initially this was attributed to Covid but as China’s economy has resumed growth – and certainly growth in its energy-intensive sectors – coal imports have dropped sharply from all countries, not just Australia. Indonesian exports were down 37% year on year in September. Public statements from China are pushing the narrative that Australia is being punished for its diplomatic insolence, but Indonesian exports are being just as badly hit despite relations with China being on a comparatively better footing.

In some of the frenzied commentary around China and its suspension of coal imports it is important to understand market dynamics rather than taking the spin from the Chinese foreign ministry at face value.

The decline in Australian coal exports has nothing to do with diplomacy and hurt feelings and everything to do with long-standing Chinese economic policy. Australia has generally been unaffected by China’s mercantilist tendencies and desire for self-sufficiency which has been a driving concern in more high-tech sectors under Xi.

We do not sell many chips, mobile phones or industrial equipment and have not felt the chill of China’s “localism” as much as Europe or the United States to date because we have limited presence in these supply chains. This is now changing as China quite explicitly pushes for self-sufficiency in key economic inputs such as energy and food. China’s rhetoric and policy looks more and more like a wartime North Korean “juche” footing.

As a major energy exporter this now matters a great deal for Australia. China’s plans for slower but more self-sufficient growth will slow their energy demand, allowing their investments in renewables, nuclear power and both the local coal capacity and logistics to move rapidly, which will reduce the need for energy imports, especially coal. How quickly they can go to zero imports is a topic of some debate but recent rail capacity expansions allowing them to use more of their own output from inland coalfields combined with low-carbon energy growth indicate that time may be now. China has throttled back imports already and shows no sign of shortages or reduced inventories. There is no reason to believe they cannot do this further.

For Australia to deal with this our political class first needs to face the reality that this is happening and no turnaround in diplomatic policy is likely to change it. Additionally this self-sufficiency policy could extend to other commodities we export to China. China’s determination to protect local industries and jobs as well as its more orthodox Maoist-Leninist turn dictates greater self-sufficiency and weaker commitments to free trade as both are far downstream of its more nationalist political priorities. This fact must enter our own economic calculus. Wishing for simpler, more liberal times when China was more committed to honouring trade agreements and growing rapidly is not an effective strategy.

To that end we need to start a discussion of how best to allow communities and workers in the coal sector to deal with this transition. The pressure is being felt already and reduced hours and job losses are impacting workers in the Hunter Valley and elsewhere. It is disingenuous to tell people that everything is fine when they know it is not.

Similarly we need to seriously consider the impacts of China’s more self-sufficiency-driven economic program and what it means for the rest of the economy. For some the developments in coal may be an unpleasant surprise but we should endeavour to not be surprised similarly again. Milk powder at some point will have to reconcile itself with China’s low fertility rates. Iron and bauxite industries will need to keep an eye on both lower growth targets and China’s efforts to reduce emissions and imports via recycling as well as efforts to second source from African mines.

Perhaps more poignantly we need to understand that wearing a high-visibility vest and helmet does not make work or employment more real or stable. Just because you can pick up a piece of coal and hold it in parliament does not make it more real and stable than working behind a screen. Commodity markets are volatile, undifferentiated products and the customers are concentrated with ageing populations and slowing growth. These industries are not beloved by investment managers for very plain reasons that have nothing to do with environmental, social or governance reasons.

Perhaps our politicians might cast a similarly dispassionate light on the sector and where Australia’s growth opportunities may lie rather than focusing on opportunities to play dress-up that PR flacks seem to prefer.

• Alex Turnbull is a fund manager based in Singapore

15 October 2020

The Guardian