The Coalition is seeing red (meat) over the methane pledge – but it’s not just about burping cattle

About half of the CO2-equivalent caused by releasing methane in Australia comes from agriculture. The rest comes mainly from coalmines, oil, gas and waste

First it was electric cars trying to tow away your weekend, and now it’s a non-binding global pledge to make modest cuts to methane emissions that will devour your steak (apologies to the vegetarians and vegans).

The Albanese government is considering signing a global pledge alongside more than 120 other countries, led by the United States and Europe, to cut all methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

But this prospect has sent members of the Coalition into a red-meat frenzy.

“Now the Aussie BBQ is under threat,” said the National party leader, David Littleproud, who said such cuts to methane would make meat too expensive.

The Liberal leader, Peter Dutton, said the pledge would “destroy” rural jobs and the Nationals MP Barnaby Joyce claimed it was a pledge “to make people hungry”.

Senator Matt Canavan told Sky’s Outsiders program, “the kind of thing we have to do is ask, Australia, do you want to eat red meat in ten years time or do you not?”.

Let’s calm the farm a little here.

About half of the 123 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent caused by releasing methane in Australia comes from agriculture – much of it from burping cattle.

The rest comes mainly from coalmines, the oil and gas sector and the waste sector.

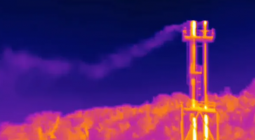

There are real concerns the growth area for methane is in the fossil fuel sector, with the added problem that emissions are likely being substantially underestimated.

There are also concerns, as the planet continues to heat up, that more methane will be released from natural sources such as wetlands and thawing permafrost.

Cutting methane is seen as a way to quickly put downward pressure on global temperatures because it is a potent greenhouse gas (causing about 82 times more warming over a 20-year period than carbon dioxide) that is also short-lived, lasting only a decade in the atmosphere.

An official briefing on the pledge says targeted measures to cut methane would see twice as many savings in the fossil fuel sector (64 million tonnes of methane) than in agriculture (32Mt).

Given the Coalition’s focus on agriculture, what does the sector’s research group, Meat and Livestock Australia, think? Would a 30% target by 2030 make meat prohibitively expensive, or be unachievable?

“No, as the proposed pledge is not a tax,” a spokesperson said. “MLA welcomes investment into methane-reducing technologies as part of Australia’s potential commitment to the pledge.”

Not all farming groups are behind the pledge – NSW Farmers is against it, and the National Farmers’ Federation is seeking assurances it won’t face new taxes or regulations.

But the MLA has a target for the red meat sector to be carbon neutral by 2030 and says its plan is “more ambitious” than the global methane pledge. Using feed additives and genetic selection for lower-emitting methane could save at least 19Mt CO2e per year.

In mining and heavy industry, the Albanese government says changes to a Coalition-era policy to cap emissions of the country’s biggest polluters will also cut methane emissions.

Tough to swallow

Canavan tweeted that Labor “wants to sign us up to a UN methane reduction agreement”.

But the pledge is an agreement between heads of state, and isn’t part of any UN process. Canavan went on, saying “according to the UN, you can only have 14g of red meat a day” to meet net zero emissions.

But no such UN recommendation exists (a factcheck from AAP took the One Nation senator Malcolm Roberts to task over the same claim earlier this year).

The “14g” comes from not-for-profit group EAT’s 2019 report on science-based targets for diets (the group’s founder took a role at a UN food summit, from which this very long bow ending with a UN recommendation has been drawn).

Dr Michalis Hadjikakou, a lecturer in environmental science and sustainability at Deakin University, said the IPCC and the UN had recommended cutting red meat consumption.

But not everyone in the scientific community agreed with the recommended diet from EAT.

“[Cutting red meat consumption] helps reduce deforestation and demand for livestock feed, both of which have much broader implications on the environment,” Hadjikakou said.

“However, attempts to scare people in this way are not helpful and are not going to help achieve the behavioural change required.”

Dutton’s EV crash

Peter Dutton was shooting the breeze on electric vehicles with 2GB’s Ray Hadley last week. The radio host claimed the energy minister, Chris Bowen, wanted EVs “to be 80% of new production by 2030”.

“These cars … are run by electricity. I mean, we don’t have enough electricity,” said Hadley.

“You’re right,” said Dutton, before offering an anecdote from a friend who had taken 45 minutes to recharge their car during an outing.

“Now, if you’re a sales rep or you’ve got two cars in front of you and you’re having to wait 90 minutes before you can charge your car up, which is 45 minutes, the country will go broke,” said Dutton. “The technology is not there yet.”

So let’s take all this in turn.

Labor doesn’t have a target on electric car production or sales, but it does have a target to have 75% of new government-owned vehicles and leases to be electric by 2025.

Modelling for the government’s Powering Australia plan did project 89% of new car sales would be electric by 2030, at which point 15% of cars on the road would be electric. But those are not targets.

And what about all the extra electricity?

Unsurprisingly, the Australian Energy Market Operator (Aemo) is not oblivious to the demands that electric vehicles will place on the electricity network.

Aemo’s plan for the future of the electricity market includes an expectation that by 2030 about 12% of all the cars on the road will be electric.

Dr Jake Whitehead, head of policy at the Electric Vehicle Council, says if all Australia’s 17 million cars and light vehicles were suddenly electric and driving between 13,000 and 15,000 km a year, this equates to a 15% increase in electricity generation.

“Importantly though, this 15% increase will occur over the next 27 years – assuming we meet our net zero target and have a 100% zero emission car fleet by 2050,” Whitehead said.

On charging times, Whitehead said assuming drivers take a break every 2 to 2.5 hours (translating to about 250 km driven) then “EVs available on the market today can charge this amount in around 10 to 20 mins ... about the right amount of time to stretch your legs.”

With ultra-fast 350 kW chargers being rolled out (as well as models matching that capacity), charging times will be under 10 minutes.

coverphoto: Now the Aussie BBQ is under threat,’ said the National party leader, David Littleproud, suggesting cuts to methane would make meat too expensive. Photograph: Bianca de Marchi/AAP