Here’s a question Cop28 won’t address: why are billionaires blocking action to save the planet?

It’s obscene that the super-rich can criminalise protest, while they burn the world’s resources and remain untouched by the law

Don’t they have children? Don’t they have grandchildren? Don’t rich and powerful people care about the world they will leave to their descendants? These are questions I’m asked every week, and they are not easy to answer. How can we explain a mindset that would sacrifice the habitable planet for a little more power or a little more wealth, when they have so much already?

There are many ways in which extreme wealth impoverishes us. The most obvious is money-spreading across our common ecological space. The recent reporting by Oxfam, the Stockholm Environment Institute and the Guardian gives us a glimpse of how much of the planet the very wealthy now sprawl across. The richest 1% of the world’s people burn more carbon than the poorest 66%, while multibillionaires, running their yachts, private jets and multiple homes, each consume thousands of times the global average. You could see it as another colonial land grab: a powerful elite has captured the resources on which everyone depends.

But this is by no means the end of the problem. Some of these pollutocrats also go to great lengths to thwart other people’s attempts to prevent Earth systems collapse. Billionaires and centimillionaires fund a network of organisations that seek to prevent effective environmental action. Many of the junktanks founded or funded by Charles and the late David Koch, owners of a vast business empire incorporating fossil fuel extraction, oil refineries and chemical plants, supply the arguments that disguise industrial self-interest as moral principle. So do their opaquely funded counterparts in the UK, in or around Tufton Street in Westminster.

The multimillionaire Jeremy Hosking, who poured millions into Vote Leave and the Brexit party, is also the main funder of Laurence Fox’s Reclaim party, which claims there is no climate emergency and campaigns against net zero policies and low traffic neighbourhoods and in favour of fracking. Coincidentally, an investigation by openDemocracy last year found that his company, Hosking Partners, had $134m invested in the fossil fuel sector.

Harder to explain perhaps are the oligarchs who are not heavily or directly involved in fossil fuels, yet foster opposition to environmental action. A recent investigation by the website DeSmog found that 85% of opinion pieces about environmental issues published in the Telegraph over the past six months either denied the science or attacked the measures and campaigns seeking to prevent environmental breakdown. The current owner, Sir Frederick Barclay, is not a fossil fuel baron. But if the newspaper is now sold, as seems likely, to a fund controlled by Abu Dhabi’s royal family, bankrolled by oil and gas, it could scarcely be worse.

At the core of Elon Musk’s empire is Tesla, which makes electric vehicles. But he has turned his recent acquisition Twitter (now X, soon to be Ex) into an intensely hostile place for environmental discussion: research suggests that almost 50% of its environmentally oriented users have either gone quiet or been driven off the platform since its emuskulation. Musk himself has contributed to the denial of environmental science that has boomed on X since he bought it.

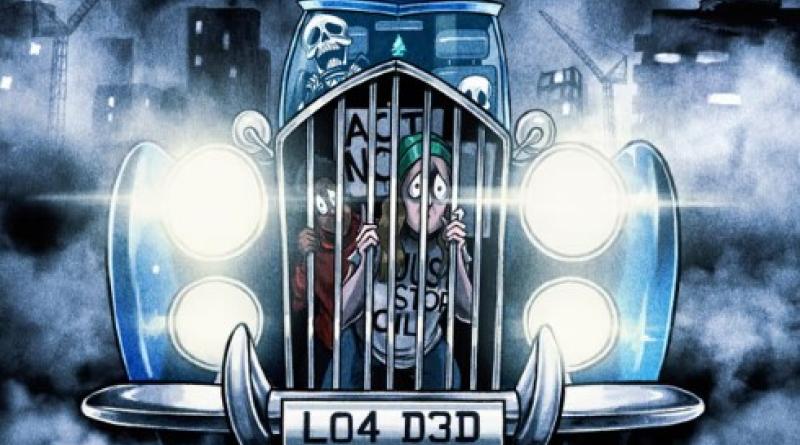

A broad coalition of interests – fossil fuel companies, billionaires and their newspapers and other members of the economic elite – has lobbied for and achieved the criminalisation of environmental protest in many parts of the world, including the UK. Here, as in several other countries, gentle environmental protests now attract long prison sentences, facilitated by silencing in court: campaigners in some cases are prohibited from telling the jury why they took their action. In the US, organisations funded by oil companies and billionaires draft laws including the most draconian and chilling penalties for protesters, then seek to universalise them across numerous states and nations. Entirely peaceful protesters are demonised as extremists and even terrorists. A widespread hostility towards environmental campaigners has been manufactured by dark-money junktanks and the billionaire press. It is obscene that those who seek to protect the living planet by democratic means are arrested en masse and imprisoned by the authorities, while the people and organisations trashing our life-support systems are untouched by the law.

So why do oligarchs who do not have direct investments in environmental destruction appear so hostile to environmental protection? Part of the reason is that any opposition to business as usual is perceived as opposition to its beneficiaries. Those who are billionaires or centimillionaires today are, by definition, well-served by the current system. They correctly perceive that a fairer, greener world means curtailing their immense economic and political power. Even those who have invested in green technologies or who donate to green causes doubtless feel an instinctive sense of threat.

Networks funded by fossil fuel companies deliberately aggregate the issues, connecting green policies with communism and violent revolution, while promoting political candidates who will clamp down simultaneously on environmental action, democracy and redistribution. The property paranoia often associated with extreme wealth – the sense that everyone is plotting to take it away from you – is easily triggered.

But we cannot discount the possibility that some of these people really don’t care, even about their own children. There are two convergent forces here: first, many of those who rise to positions of great economic or political power have personality disorders, particularly narcissism or psychopathy. These disorders are often the driving forces behind their ambition, and the means by which they overcome obstacles to the acquisition of wealth and power – such as guilt about their treatment of others – which would deter other people from achieving such dominance.

The second factor is that once great wealth has been acquired, it seems to reinforce these tendencies, inhibiting connection, affection and contrition. Money buys isolation. It allows people to wall themselves off from others, in their mansions, yachts and private jets, not just physically but also cognitively, stifling awareness of their social and environmental impacts, shutting out other people’s concerns and challenges. Great wealth encourages a sense of entitlement and egotism. It seems to suppress trust, empathy and generosity. Affluence also appears to diminish people’s interest in looking after their own children. If any other condition generated these symptoms, we would call it a mental illness. Perhaps this is how extreme wealth should be classified.

So the fight against environmental breakdown is not and has never been just a fight against environmental breakdown. It is also a fight against the great maldistribution of wealth and power that blights every aspect of life on planet Earth. Billionaires – even the more enlightened ones – are bad for us. We cannot afford to keep them.

-

George Monbiot is a Guardian columnist

Illustration: Ben Jennings/The Guardian