What is the future of nuclear power?

This is the question Energy Monitor has tried to answer over the past week, with a series of in-depth articles to mark the tenth anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan. Here is our conclusion.

Over the past week, Energy Monitor has run a series of in-depth articles to mark the tenth anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan. The climate crisis has injected fresh impetus into the debate over the role of nuclear power in energy production. The nuclear industry wants its slice of the action and is lobbying for its part in a post-Covid green recovery.

Half a century of experience, no CO2 emissions, continued investment in innovation and strict controls are some of the things nuclear has going for it. In France, not a single scrap of material from a nuclear power plant is authorised for reuse in another application. Accidents can be catastrophic but are rare. Long-term disposal sites for radioactive waste are under development, with Finland planning to operationalise the world’s first in 2023. Nuclear plants also produce some of the cheapest power around.

However, for many the technology is still irrevocably bound up with nuclear weapons and the Cold War. It is associated with well-known accidents from Three Mile Island in the US to Chernobyl in Russia to, most recently, Fukushima. It generates radioactive waste that remains dangerous for hundreds of thousands of years and the first deep geological disposal facility for that waste is still a plan rather than reality.

An industry in decline

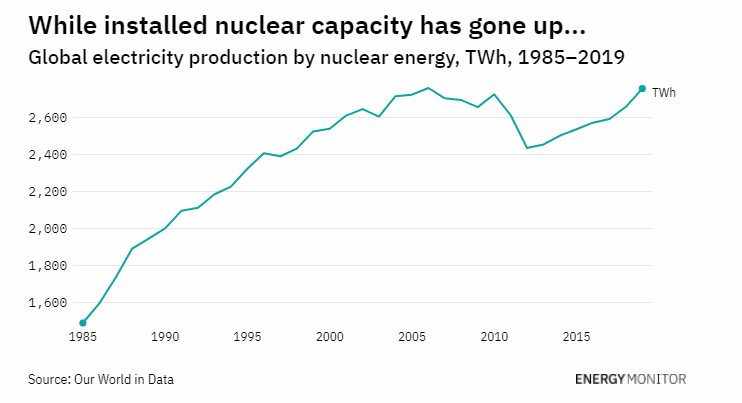

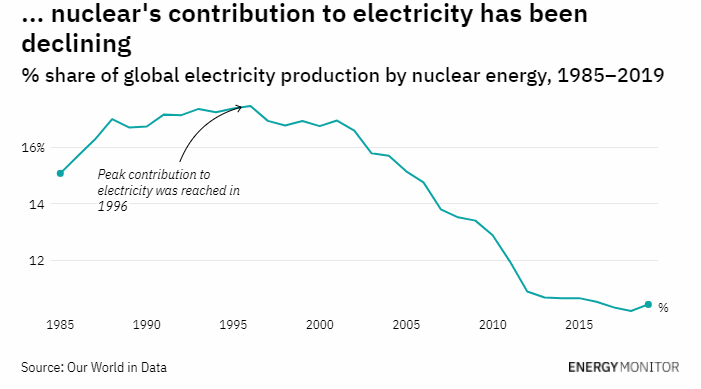

So, what does the future hold? If the past is a guide, it does not look rosy. The numbers tell the story of an industry in global decline. In 2019, for the first time in history, non-hydro renewables like solar, wind and biomass generated more electricity than nuclear power plants. The amount of nuclear power peaked in 2006 and there were fewer reactors operating at the end of 2019 than 30 years ago.

These figures headline in the World Nuclear Industry Status Report (WNISR), a detailed annual account of the commercial nuclear power industry led by Mycle Schneider, a prominent international nuclear expert, and nuclear sceptic. However, a similar tale emerges in other studies, including from nuclear adherents such as the International Energy Agency (IEA), which issued its first report on nuclear power in almost 20 years in May 2019.

The IEA too, documents the escalating costs and delays of nuclear new-build. The two most famous examples are Flamanville 3 in France and Olkiluoto 3 in Finland. Both showcase the latest French EPR reactor design, and both are over ten years behind schedule and three to four times over budget (each is now expected to cost at least €10bn). In China too, reactors that started up in the last few years took twice as long as expected to build.

These new-build problems have devastated the industry, forcing two of its powerhouses, Westinghouse and Areva, into bankruptcy.

Climate emergency

Where views diverge is on what the past means for the future. The IEA – and the nuclear industry – argue that the scale and speed of emission reductions required by climate change make nuclear power indispensable. Over the past 50 years, the use of nuclear power has reduced CO2 emissions by about 60 gigatonnes, or nearly two years-worth of emissions, the IEA says. Without nuclear, emissions from power generation would have been almost 20% higher.

The world risks a “steep decline” in nuclear power in developed countries that could lead to “billions of tonnes” of extra carbon emissions, the agency warns. Without new nuclear, the energy transition becomes “more difficult and more expensive”.

Schneider and his fellow sceptics argue the exact opposite. They say nuclear is too slow and expensive to tackle climate change. Worse, it could exacerbate it by draining resources away from faster, cheaper solutions, namely renewables and energy efficiency. The WNISR calls the nuclear sector “one of the most potent obstacles to renewables’ further progress”.

They point out that as renewables are getting cheaper, nuclear is getting more expensive. Renewables top investments and production capacity additions. Lifetime extensions to nuclear reactors struggle to be cost-competitive. Even China, which has the world’s most ambitious nuclear programme, is producing more power from wind.

Politics will decide

China is most likely to decide the future of nuclear power globally. It did not meet its 2020 nuclear targets, but is building new plants and has plans for more. EDF’s problematic EPR reactor is up and running in China. In Europe, trade association Foratom imagined five new reactors a year back in 2010. Instead, closures dominate the headlines. All eyes are turned to France, which still generates 70% of its electricity from nuclear plants, to understand the technology’s future prospects – and potential EU support.

Over in the US, the industry is poised for a pivot, rather than a rebirth, as our US correspondent Justin Gerdes reports. The Department of Energy has decided to support the development of “small modular reactors” with outputs ranging from tens to hundreds of megawatts. These are an innovation that have been on the horizon for some time, but whether they will take off at a meaningful scale remains to be seen.

Either way, the era of Big Nuclear is over, argues editor-in-chief Philippa Nuttall Jones in a round-up piece for the New Statesman.

[Keep up with Energy Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

Nuclear’s future hinges on whether it can deliver cost-effective emission reductions fast enough to help climate change. The industry also needs to show it can deal with its waste. This issue will be particularly thorny in the EU where there will be increasing pressure on industry to showcase green credentials before receiving investment. Europe has also lost one of its strongest nuclear advocates, the UK, thanks to Brexit.

The disaster at Fukushima swept through the industry like wildfire. It triggered Germany’s definitive decision to exit nuclear power by 2022 and is the reason nuclear power made up less than 5% of Japan’s electricity mix last year, down from 30% before Fukushima. Barring similar events, the future of nuclear power is ostensibly decided by economics. Except that nuclear always has been and will be political.

Energy Monitor’s series on nuclear power in the energy transition in March 2021:

- A decade after Fukushima, Japan still struggles with its energy future By Katie Kouchakji. The country’s electricity generation profile has shifted in favour of fossil fuels. Will its net-zero emissions goal change that?

- Will there be a second act for the US nuclear power industry? By Justin Gerdes. The industry’s future in the US likely rests on new reactor designs such as small modular reactors that proponents say will slash costs and boost safety.

- Will China gamble on a nuclear future? By Joceyln Timperley. Nuclear power is likely to play a role in the country’s plans to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, but renewables are crowding in. How big a role versus renewables and other energy sources is an open question.

- France still hedging its bets over nuclear industry future By Philippa Nuttall Jones. Nuclear is the bedrock of France’s electricity system, but its reactors are old and nuclear’s share in the power mix will shrink. Will the government go all out for renewables or splurge on new nuclear?

- Brexit may tip the scales towards an EU nuclear phase-out By Dave Keating. The EU has lost one of its most powerful pro-nuclear voices just as it is about to vote on two key measures that will determine whether nuclear has a European future.

22 March 2021

ENERGY MONITOR