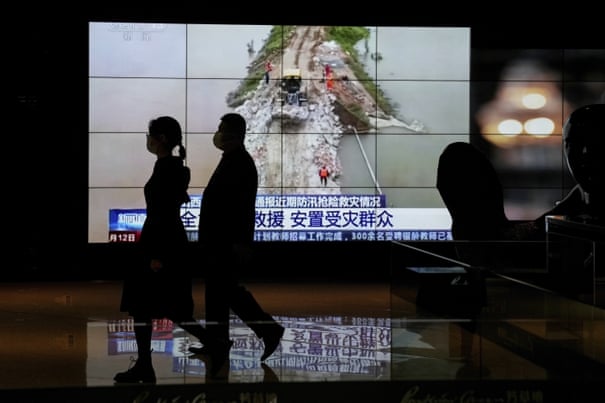

‘It’s alarming’: intense rainfall and extreme weather become the norm in northern China

Meteorologists link such weather patterns to the climate crisis, which exacerbates the frequency and severity of climatic extremes and variations

The unusual rains began to fall in Shanxi on 3 October, and the torrential downpours lasted for three days.

According to Chinese media, the 59 observatories across Shanxi province all recorded historic levels of rain. According to the local weather bureau, the average rain in the province reached 120mm (4.7 in) between 2 and 7 October. The average rainfall across the US over a whole month is 71mm.

But when the rain finally stopped more news began to emerge about the damage it had caused. A week later, the Communist party newspaper Shanxi Evening News reported that an estimated 190,000 hectares (470,000 acres) of crops had been inundated and destroyed.

For 47-year-old Yu Jianhua (not her real name) in the village of Yaocheng, an hour’s drive south of Taiyuan, this loss has been devastating. Her two dozen greenhouses – the family’s main source of income – have all been destroyed by the floods. In the last few days, she was busy rescuing the remaining celery with the help of fellow villagers, in a hope that it was still fine to be sold on the market in the weeks to come.

Yu, who lives there with her two elderly parents-in-law and her husband, was evacuated during the rain. But when she went back after the downpours, she found that small cracks had begun to appear all over her house, where a portrait of Chairman Mao hung at the centre of the barren wall above a Chinese character, fu (meaning good fortune).

“I didn’t think too much about it at the time. But then, cracks started to expand day after day and I began to worry. So my husband and I moved away to stay at our friends’ last Friday.” But she’s also in a dilemma: her in-laws insisted on staying in their old home, even though it is becoming a bit wobbly. “They are very stubborn – they don’t want to leave the house they spent most of their lives in.”

Two weeks after the rain, local officials came to inspect her house, and they are now talking about a mixture of compensation and subsidy. But it takes time to rebuild. “I’m really exhausted,” said Yu, adding that what she had just experienced “definitely has to do with climate change”.

It is not the first time China has had such a dramatic scene this year. In July, the heavy rainfall and the deadly floods in the central province of Henan – one of the country’s largest agricultural provinces – killed more than 300 people, with a few dozen still missing. Chinese meteorologists link such unpredictable weather patterns to the climate crisis, which exacerbates the frequency and severity of climatic extremes and variations.

“This year, in particular, extreme weather in the north of China’s Yangtze River has been common,” said Prof Faith Chan of the University of Nottingham in the eastern Chinese city of Ningbo. “In Shanxi, monthly rainfall is normally about 31mm in October, but this year [it is] at least three times more than usual, reaching 119.5mm, to be precise. It’s alarming.

“Although we still need more scientific research into this phenomenon, so far it all indicates a trend that extreme weather and intense rainfall will be a norm in northern China. China has to act fast.”

Beijing has already taken steps to tackle the climate crisis. In 2013, President Xi Jinping promised to achieve “ecological civilisation” in China. Before Cop26, Beijing promised to reduce fossil fuel use to below 20% by 2060. In the last couple of years, Chan said, cities across China have also been beefing up their emergency response capability.

Still, critics say more can be done on the part of the government in building resilience. They include, Chan said, allowing the media to get the message out soonest possible and establishing a protocol for disaster relief. “More importantly, Beijing should work closely with communities, and communities also need to engage and participate closely co-produce flood resilience practice to reduce loss and damage from disasters.”

Yan Tan, an associate professor in human geography at the University of Adelaide in Australia agrees. “What we saw in China this year is not unique, in particular in developing countries across Asia Pacific. Think about Bangladesh and the Philippines,” she said.

“As a result of increasing climatic extremes, unfortunately, a lot of people will have to be displaced or forced to migrate if governments could not make effective policy and programs that avert, minimise, plan for, and put proactive and contingency arrangements into place for human mobility in a climate-resilient, sustainable future.”

But to many flood victims leaving is unrealistic, said Luo Qiang (not his real name), 38. Luo was born in Nanzuo village, Qi county, 20 miles south of Yaocheng village. He moved away years ago but says: “Most of our villagers are over 60 years old here. This is where they were born, bred and where they plan to be buried in the future. They don’t want to go anywhere.”

Nanzuo was only just officially lifted out of the national poverty level last year. For generations, Luo’s family worked as farmers here, planting corn and raising pigs for a living. But the recent rain and floods destroyed their main sources of income and livelihood.

“This is so rare. I’ve never seen it,” he said. He rushed back home to help immediately after the rain had stopped, only to find many villagers had already been relocated to a school in the county because their homes were flooded. “Clothes, quilts were all soaked. Pigs killed. Our corn, too.”

“I’m 1.73 metres tall. When I came back on 7 October, the water could reach my chest. Now the water is receding, but in some fields, it still reaches my knees,” Luo said. “Meanwhile, cracks are appearing in many of our villagers’ houses. They are really worried about what could happen next.”

It’s a double whammy for villagers across the flooded areas in Shanxi this month. By now, their main sources of income and livelihood have been ruined by the rain and the floods. Worse still, winter has arrived in Shanxi, and the price of coal has become too high after a recent national crackdown on its use, in an effort to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

“Last year, we spent 3,000 yuan [£346] on heating for the duration of five months. This year, it’d reach 8,000 to 9,000 yuan. There are new energy options, but we cannot afford them,” Luo said. “We cannot plan ahead any more.”

9 November 2021

The Guardian