Like a 'second wife': Wind energy gives American farmers a new crop to sell in tough times.

CLOUD COUNTY, Kansas — Across this central northern county in Kansas, wind turbine blades slowly slice the cold air over winter-brown fields. The 67 wind turbines of the Meridian Way Wind Farm straddle dozens of farms and ranches, following the contours of the land and the eddies of the wind above it. The turbines are tall enough that driving by, their size is hard to gauge.

Their impact on the surrounding landowners is less hard to measure.

“I would say the absence of financial stress has been a real game-changer for me,” said Tom Cunningham, who has three turbines on his land in Cloud County and declined to give his age, saying only he was "retired." “The turbines make up for the (crop) export issues we’ve been facing.”

In an increasingly precarious time for the nation’s farmers and ranchers, some who live in the nation’s wind belt have a new commodity to sell — access to their wind. Wind turbine leases, generally 30 to 40-years long, provide the landowners with yearly income that, while small, helps make up for economic dips brought by drought, floods, tariffs and the ever-fluctuating price of the crops and livestock they produce.

Each of the landowners whose fields either host turbines or who are near enough to receive a "good neighbor" payment, can earn somewhere between $3,000 to $7,000 yearly for the small area — about the size of a two-car garage — each turbine takes up.

Cunningham's lease payments have allowed him to pay off his farm equipment and other loans. The median income in Cloud County is about $44,000, according to the 2018 U.S. Census.

“Some of the farmers around here refer to the turbines as ‘their second wife.’ That’s because a lot of times farm wives have to work in town to make ends meet,” he said.

Rural areas across the United States have long experienced population declines, slow employment growth and higher poverty rates than urban areas, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Things have been especially difficult recently. U.S. farm bankruptcy rates jumped 20% in 2019, to an eight-year high. Wisconsin saw 48 Chapter 12 filings, or family farm bankruptcies, over the 12-month period ending in September, the nation's highest rate. Georgia, Nebraska and Kansas were next, each with 37 filings. Minnesota, California, Texas, Iowa, Pennsylvania and New York rounded out the top 10 states for farm bankruptcies.

An ongoing trade war between China and the U.S., brutally low prices for commodity crops and increasingly unpredictable weather patterns have all contributed.

"Farm incomes have been down for a couple of years," said John Newton, chief economist for the American Farm Bureau Federation.

For some, lease payments to a wind farm to put up a turbine increasingly provide a cushion against the harsh economics of farm life.

Across Kansas, wind turbine lease payments are between $15 and $20 million a year, according to the American Wind Energy Association. Nationally it's $250 million.

The money matters. About 180 miles south of Meridian Way is the Elk River Wind Farm. Pete Ferrell, 67, of unincorporated Butler County, says wind helped save the ranch, just as oil helped save it back in his father’s day.

“Dad allowed oil production here. There was a big drought in the 1950s. He said, ‘In all honesty, it was the money from the oil that got us through,’” he said.

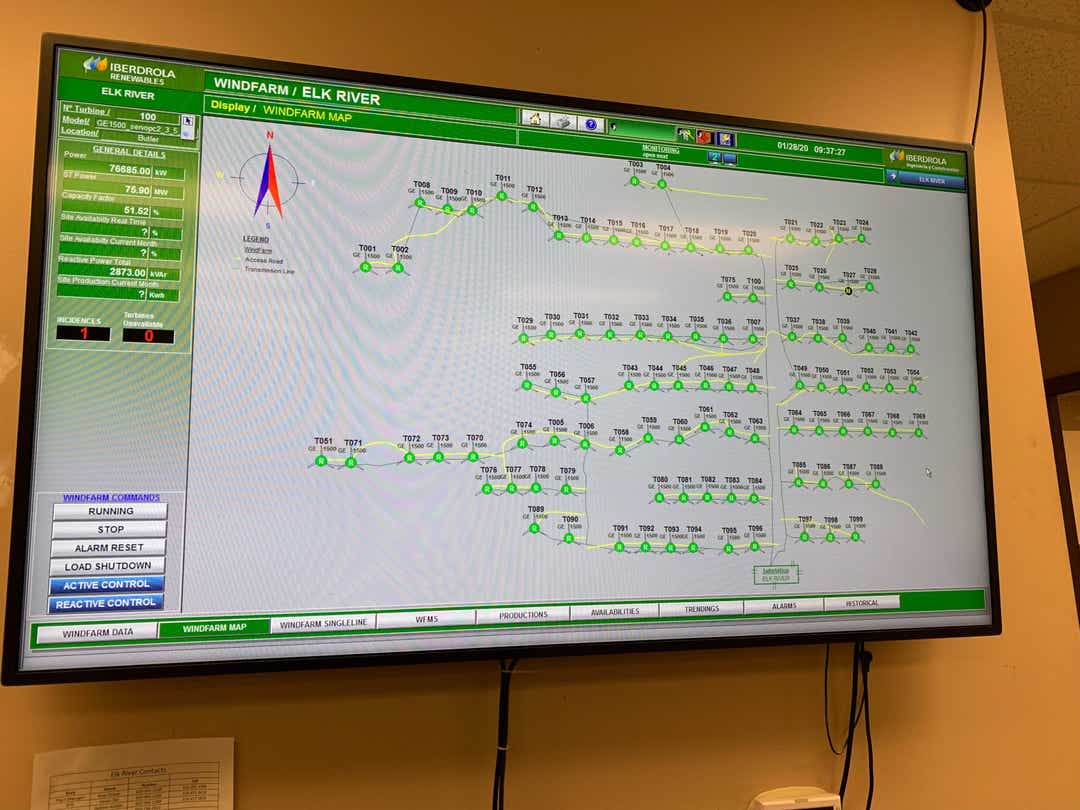

To Ferrell, harvesting the almost constantly-blowing Kansas wind is another way to make a living out of the land. Elk River's 100 turbines sport enormous blades, each 125 feet long, that sit atop 260-foot towers.

From any distance away, they appear silent as the raw winter wind whips by. Standing directly underneath, their susurrations combine the sounds of flags snapping in a strong breeze and the whirr of a rumbling ice cream maker on this cold day. The nearby air fills with the electric motor thrum of the oil pump jacks they are interspersed with.

Jasper Colt, USA TODAY

For Ferrell, leasing land for wind turbines is reminiscent of the side jobs and town jobs many farmers and ranchers have always needed to get by.

“I really wasn’t going to survive as a rancher without outside income, or I was I going to work myself to death doing 15-hour days," he said.

It's that way across the Midwest, said Kerri Johannsen, energy program director with the Iowa Environmental Council. "It’s not so much about green energy at all, but economics."

Iowa is a state that produces things from the land. Now, she says, wind is "just another crop, another opportunity to capture resources.”

Wind energy is cheap and growing

The phrase "wind farm" is confusing because wind farms don't look much like farms, or even traditional power plants. They typically consist of between 50 and 100 turbines connected by buried wires that link up to a central transmission and one or two low-slung maintenance buildings. Each three-bladed turbine is set on a high tubular metal tower. The turbines run in offset lines, usually about half a mile apart so they don't steal each other's wind. Underneath them, cattle graze or crops are grown.

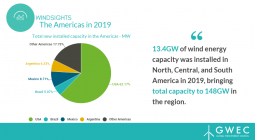

Wind went from 2.3% of the U.S. electricity mix in 2010 to almost 7% in 2019. It’s also one of the cheapest ways to produce energy, now sometimes even less than natural gas.

Elizabeth Weise, USA TODAY

They're also increasingly a part of America's rural landscape, in part because the Great Plains is very windy, there's ample ground and little to get in the way of the river of air that flows above the fields.

Kansas is expected to have 40 wind farms by the end of this year, said Dorothy Barnett, executive director of the Climate + Energy Project, a non-profit clean energy organization in Hutchinson, Kansas.

The Sunflower state is the nation’s fourth-largest producer of wind energy and in 2018 generated more of its total electricity from wind than any other state, 36.4%, according to the American Wind Energy Association. All told, Kansas produced almost 20 gigawatts of electricity from wind in 2018, the last year for which numbers are available.

At Meridian Way, things started in 2007 when Jim Franey and his neighbors were invited to a smothered steak dinner at the Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Parish Hall to hear about a possible wind farm in their area. In the end, 67 of 68 landowners signed up.

Elizabeth Weise, USA TODAY

“A lot of people were concerned about the aesthetics," said Franey, 72. "I said to ‘em, ‘Sign up. Because if it’s on your neighbors’ land you’ll see it, but you won’t get a check. Might as well get a check.’”

Meridian Way’s 67 turbines now produce 201 megawatts of electricity annually, enough to power 59,000 homes each year. Meridian Way is owned by EDP Renewables North America, based in Houston, Texas. The company develops, constructs, owns and operates wind farms and solar parks throughout North America. It's owned by a Spanish company, EDP Renováveis, which is the world's fourth-largest wind energy producer.

A sometimes controversial form of energy

Wind turbines produce cheap, pollution-free energy at a time when more than 30 states have set goals are standards requiring between 2% (South Carolina) and 100% (California, Hawaii, Maine and Washington) of their energy be from renewable sources.

They are also increasingly controversial. Some people don’t like how they look, others point to theories that they cause cancer and other ills — a statement President Donald Trump echoed last year in a speech, although more than 25 scientific studies have found no correlation between living near a turbine and risks to human health.

In November, the largest study to date looking at the feelings of people who live within five miles of wind turbines found high overall acceptance of wind power projects. Funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and conducted by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, researchers surveyed 1,705 people, 36% of whom lived less than half a mile of a turbine and 30% who lived within a mile.

Roughly 57% had positive or very positive attitudes about them, 34% neutral and 8% negative or very negative.

For people who lived within half a mile, 75% had either neutral or positive feelings about the wind project while 25% had negative or very negative attitudes.

Efforts to stop new wind farms have ramped up in the past few years, with an 80-turbine project in Reno County, Kansas, voted down by the County Commission last year because of homeowner concerns about property values and possible health effects.

But while the U.S. wind belt includes much of the Midwest, an area that is generally conservative, wind power isn’t generally seen here as either liberal or conservative.

“Remember, 90% of the wind farms in this country are in Red states,” said Ryan Orban, plant manager at the Elk River Wind Farm where Farrell’s ranch is located. The turbines take up slivers of land on the five ranches whose fields they dot. The wind farm is owned by Avangrid Renewables, based in Portland, Oregon. It is part of Iberdrola Group, a Spanish energy company.

For many, it’s simply about property rights.

“I don’t want anybody doing is telling me what I can or can’t do with my land,” said Jack Thimesch, a farmer and rancher in Kingman County, Kansas, who’s also a Republican state legislator.

He’s got one turbine on his 800 acres, right along where he raises cattle and farms wheat.

Jasper Colt, USA TODAY

“My brother got one and I got one, we have ground right next to each other,” he said.

“It makes for a pretty nice check every year,'” one that helps keep everything afloat, he added.

Some of his neighbors said no when the wind company first came through to site the farm, something he now says they regret.

“There isn’t a person out here who wouldn’t have sited more on their land if they could,” he said.

Many of the objections he hears — that the turbines are noisy or scare animals — come from people who clearly don’t have the first-hand experience, Thimesch said.

Of his own turbine, he said, “I can hear the motor humming. But I can also hear the irrigation running from my neighbor’s fields and that’s louder than my turbine.”

As for whether it bothers his cattle, he says they actually love it. “When it’s hot out, they come and line up in the shade from the turbine tower,” he said.

EDP Renewables North America

The formation is called a "bovine sundial" and multiple ranchers USA TODAY interviewed described the same phenomenon on their land. The cattle bunch up in the line of shade, slowly shuffling from west to east as the sun moves across the horizon.

Wind power doesn’t benefit everyone

One issue all wind farms face is the economics of an unevenly distributed resource, a reality that can make for bad blood in communities.

Wind farms do generate taxes or payments to government, which many counties use for roads and other infrastructure, hospitals and schools. But that’s different from not getting a yearly check when your neighbors do.

The problem with wind, like the problem with oil, is that not everyone ends up with a turbine or a pump jack on their property because not every bit of land is right for wind or oil extraction.

That can create bitterness, said Thimesch. “The ones that didn’t get one don’t see value. The ones that got ‘em, see value,” he said.

In some areas, wind farms have begun making smaller payments to landowners who don’t have turbines sited on their land but who are near a farm, just to even things out.

“In Michigan, you’ve seen some companies try to offer some modest amount of payment to non-participating residents as a way to help establish buy-in,” said Jason Brown, a research and policy officer in the economic research department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

At Meridian Way, the developers did the same thing. Landowners who don’t have turbines sites on their land but who are within a certain distance, about half a mile of one, also get annual compensation.

“It’s the good-neighbor clause,” said Michelle Graham, Meridian Way’s operations manager.

Another issue is even on land with a turbine, the money doesn’t necessarily go to the person farming or ranching the land.

That’s because many U.S. farmers and ranchers rent or lease at least some of the land they work rather than owning it. Nationwide, 40% of all agricultural land is rented, according to the USDA Census of Agriculture. In some wind-rich states the number is higher.

In Iowa, for example, 55% of the land that's farmed is rented, said Dave Swenson, a regional economist at Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. So while the turbines provide a nice annual income stream to the landowner, the money isn’t always going to the person who’s living there.

“Wind energy is beneficial to only a small subset of landowners and not necessarily farmers,” Swenson said.

Thimesch, however, noted that while the person farming the land might not be receiving the checks, the owners often stay in the area. He sees neighbors retiring and renting out their land and living off the rental income and the supplementary income from the turbines.

“To them, that is priceless. For the next 30 years they know they’re going to draw an income, and it will be handed down to their kids,” he said.

Wind alone can't fix rural America

What wind power won’t do is revitalize rural America, say economists. While money to landowners and going into the tax base is helping to generate local income that could help with economic resilience in those areas, it’s unlikely to be transformational, said Brown of the Kansas City Fed.

“I’m not sure that wind power — or any one-off rural development — is going to make a big difference,” he said.

State officials tend to agree, being careful to say that wind energy is just one piece of their economy.

“I’m not sure I would call it a revolution, but in terms of supporting rural Kansas, it is a really important development,” said Randi Tveitaraas Jack, a development manager with the Kansas State Department of Commerce.

There are turbine manufacturing and assembly plants in 42 states, according to the American Wind Energy Association. Onsite and traveling wind technicians, who typically have a two-year degree and earn upwards of $50,000 straight out of school, bring solid jobs to rural areas, according to the association.

But that can’t make up for decades of rural decline. Wind money isn't enough to change outcomes, in terms of the durability and stability of rural life, in places like South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas and the like, said Swenson of Iowa State.

“It’s great in the short run and we’re going to welcome it. But in terms of stabilizing rural economies, it’s not even close,” he said.

Keeping families in the farming business

That said, research shows that for farmers who own and farm land with turbines, wind makes a tremendous difference to their long-term plans.

First, they’re more likely to have a succession plan in place on their property, said Sarah Mills, a public policy researcher who looks at land use and energy policy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She wrote her dissertation on what farmers do when they get money from wind turbines.

“What they told me was that the guaranteed income that comes from hosting a turbine was convincing their kids that farming wasn’t such a risky business,” she said.

Her research also found that farmers with turbine income invested more in their barns, tractors and other farming operations than neighbors who didn’t.

“The sense was, ‘I can take a loan out now because I know I’m going to be able to pay it off in the future,’” she said.

For Tom Cunningham, who’s been farming between Glasgow and Concordia Kansas for 40 years, the Meridian Way wind farm income has made an enormous difference.Before the wind turbines, things were rough, he recalled. Depending on the national and international economy, some years he broke even, some years he made money and, for more years than he cares to think about, he was on the edge. He's had to take a job in town to make ends meet and for a time was what he calls “functionally bankrupt.”

“This isn’t money that other people would think is very much,” he said. “But it made an enormous difference to us.”

Wind turbines operated by EDP Renewables can be seen behind a rancher's cattle on Meridian Way Wind Farm on Jan. 31, 2020 in Concordia, Kansas.

Jasper Colt, USA TODAY

16 February 2020

USA TODAY