Can These Animators Get Africa To Finally Honor Its Female Heroes?

Why You Should Care

You've never heard of these African female heroes - yet they've shaped the continent as much as men.

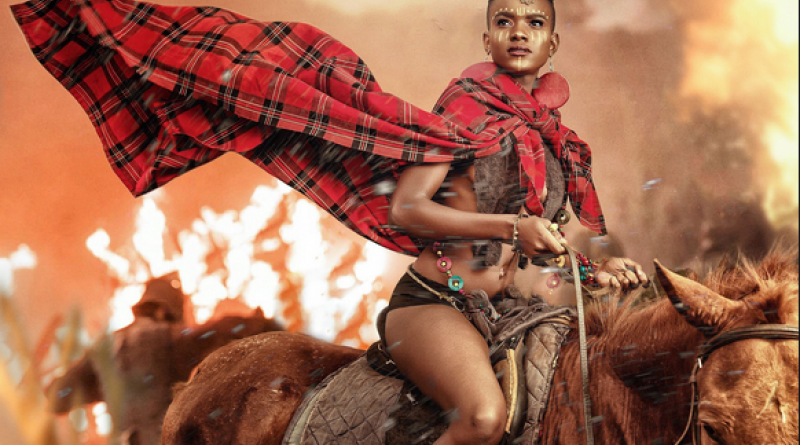

Born to poor parents in a coastal Kenyan village in the mid-1850s, Mekatilili wa Menza would rise to lead an army of women and men against British colonial rule. Exiled and imprisoned several times, the charismatic widow warrior once escaped and trekked 600 miles through forests to return to her people and revive their fight, leading to a major uprising in October 1914.

Under her leadership, her Giriama ethnic community would never be subdued by the British. Yet she’s largely forgotten, her story covered only in passing in Kenyan textbooks. Award-winning photographers Richard Allela from Kenya and Kureng Dapel from Nigeria are trying to change that, celebrating her with a first-of-its-kind animated photography project. Launched in 2017 as an online project, the images went viral, and a physical exhibition continues to move through art spaces, including at international platforms such as Alliance Francaise.

They’re part of a growing band of young African animators and visual artists breaking with the hegemony of a male-dominated telling of the continent’s history to honor forgotten or ignored female heroes. They’re using the explosion of social media, increased access to technology, and the democratization of content-sharing on platforms like YouTube, Facebook and Instagram to get past traditional media gatekeepers and reach audiences.

"WE WANT PEOPLE TO QUESTION WHAT THEY HAVE BEEN TOLD ABOUT AFRICAN WOMEN."

Samba Yonga, Co-Founder, Women's History Museum

In Zambia, media specialist Samba Yonga has partnered with historian and cultural activist Mulenga Kapwepwe to launch a Women’s History Museum, the first such initiative in Africa. The museum, which started in late 2016, currently works as a digital archive, but the Lusaka National Museum plans eventually to host it. Yonga and Kapwepwe also run a podcast called Leading Ladies that celebrates female icons. Be Dyango, who ruled the area around Victoria Falls prior to British occupation, and Mwenya Mukulu, who was the chieftainess of the area around the south end of Lake Tanganyika, figure in the podcasts, also broadcast on Facebook and YouTube accompanied by animated videos.

Nigerian-born, U.S.-based animator Roy Okupe is hunting for stories of African women in history who questioned the traditional role society thrust upon them. His most recent animation is based on Amina of Zaria, the Hausa warrior queen who ruled in the mid-16th century. Kenyan award-winning filmmaker Ng’endo Mukii last year created an animated movie celebrating the Nobel laureate environmentalist Wangari Maathai.

“To me, women are heroes. … From boardrooms to institutions and government, people are seeing how women are bringing positive change,” says Allela, the photographer. “The truth is, they have always done this for centuries, but their stories have been omitted.”

That erasure from public conscience is not unique to Africa — how would patriarchy justify its existence if history shows that women have been leaders and active participants in all spheres of society, whether that’s politics and governance or the military? But that challenge is accentuated in conservative societies. A few years ago in Kenya, a petition demanding that a road be named after Maathai served as an unexpected “aha” moment for several Kenyans, considering that almost every street — indeed everything of note in the country — is named after men.

Now, this new generation of visual artists and animators is challenging that pattern across Africa. Okupe’s video on Amina has received 419,000 views on YouTube. Certain episodes of the Zambian Leading Ladies podcast have garnered over 20,000 views. And the photography project on Mekatilili wa Menza has been seen by more than 2.3 million people.

Watch the video here.

By pointing out in the podcasts that these female icons are best described by titles such as “the general,” “the feminist,” “the diplomat” or “the warrior,” Yonga says, “we want people to question what they have been told about African women.” The museum is also working with Wikipedia on the Wikigaps project that aims to close the gender gap in the world’s largest encyclopedia. Only 1 in 5 entries in Wikipedia are about women, including only a handful of the 300 Zambians profiled on the platform. The museum team is leading an edit-a-thon to add another 150 Zambian women.

For sure, changing deep-seated social prejudices won’t be easy. But these artists and animators have no shortage of heroes to highlight. In her 1985 book, Passbook Number F. 47927, Kenyan writer Muthoni Likimani details forgotten greats: commercial sex workers who doubled as spies, everyday women who fed Mau Mau freedom fighters in the forest, domestic workers who navigated both white and Black worlds in a time of segregation.

Nor are they lacking for personal inspiration. For Allela, it’s his mother, who single-handedly raised him and his four siblings after he lost his father when he was 12 years old. Okupe, the animator, says he is inspired by his mother, sisters and wife: “They are all strong women who have positively influenced my life, but I rarely see women like them in popular media.”

SOURCE SAMBA YONGA AND MULENGA KAPWEPWE

And the rise of digital animation and the growing global love for the super-hero(ines) film genre present a rare window of opportunity for these artists. Because the stories of female heroes have been written out of history books for generations, there are gaps in what is known about them, making traditional storytelling methods complicated, Kenyan filmmaker Mukii points out. “Animation allows us to reimagine their stories even with scant information,” she says.

Her project on Maathai drew on collaboration with Brazilian artists in Acervo da Laje, a space that brings together local artists from Salvador, Bahia, a part of Brazil that embraces and owns its African ancestry. It was also a response to an animation that Mukii worked on with Kenyan artists at the art collective Pawa 254, honoring the slain Brazilian activist Marielle Franco.

“Across continents, we are drawing inspiration from each other as we tell the stories of great women,” adds Mukii. “We can use these stories to empower ourselves and empower women by changing the dominant narrative they have believed to be true.”

8 March 2020

OZY