Too hot for humans? First Nations people fear becoming Australia's first climate refugees.

- Aboriginal people in Alice Springs say global heating threatens their survival

- The town had 55 days above 40C in the year to July 2019

- Central Australian outstations are running out of water

- Poor quality housing in town camps cannot be cooled effectively

- Indigenous leaders fear extreme heat will cause influx of internal refugees

Josie Douglas sits on a verandah overlooking a ridge of red rocks and earth, scrubby with saltbush and spinifex near the centre of Alice Springs. It’s late afternoon and only 31C – a reprieve from a run of days in the high 30s and 40s.

But Douglas knows that from now on it will only get hotter.

Last summer was the hottest on record, and the driest in 27 years in central Australia. Five per cent of the town’s street trees died. A heat monitoring study showed that on some unshaded streets the surface temperature was between 61C and 68C.

“We can’t keep going on the way we’re going,” says Douglas, who is manager of policy and research at the Central Land Council.

“Central Australian Aboriginal people are very resilient. They have evolved to cope with the harsh and variable desert climate, but there are limits.

“Without action to stop climate change, people will be forced to leave their country and leave behind much of what makes them Aboriginal. Climate change is a clear and present threat to the survival of our people and their culture.”

Across central Australia, people are bracing themselves for another scorching summer of drought.

At least nine remote communities and outstations are running out of water. A further 12 have reported poor quality drinking water as aquifers run low and the remaining supply is saline.

Temperature records have already been broken. In the year to July 2019, Alice Springs had 129 days over 35C, and 55 days over 40C.

It wasn’t meant to be like this – at least, not yet. The national science agency, the CSIRO, predictedthat these temperatures would not arrive until 2030.

As the Northern Territory’s environment minister, Eva Lawler, said last September: “If we don’t do anything, the NT will become unliveable.”

The problem is where to start.

In Alice Springs opinion is divided among local politicians about the impact climate change is having on life in the desert.

Sitting on the grassy lawn outside the council, Jimmy Cocking of the Arid Lands Environment Centre talks openly about climate refugees: those who have already come into town, and those who will have to come in the near future.

“We’re going to end up with a whole bunch of internally displaced people within the Northern Territory in remote Australia, if we’re not planning for that,” he says.

“If regional centres like Alice Springs and others aren’t planning to be able to deal with the influx of climate refugees internally within our region, we’re going to be left flatfooted and unable to deal with any of the challenges and social consequences that will come from that.”

Cocking is on the town council and has sought to pass motions to declare a climate emergency. But the mayor, Damien Ryan, is reluctant to sound the climate alarm.

“In local government speak, when you have an emergency, you close it down,” Ryan says.

“I have not had any of the people who talk about an emergency say what is the next step. So you declare an emergency, what do you do then the next day? That’s never been made clear to me.”

At its October meeting, the council did not agree on the word “emergency” but voted unanimously to say there was an “escalating urgency for climate action”.

Douglas and the CLC say Aboriginal communities are doing what they can.

“People are already mitigating climate change through traditional burning and they are investing their income from land use agreements to install solar power, plant bush tucker gardens in communities and operate swimming pools, but all that counts for little in the face of the lack of climate leadership from the government,” she says.

"You see people hosing their brick houses"

The NT government says it has allocated $15m to “revitalising” the Alice Springs city centre. Some of those funds will go towards shade and landscaping to help cool the streets, and to public water stations. Ryan says the council is encouraging local schools to plant more trees.

The Territory government says it has a climate change response strategy and is working with other governments and the Bureau of Meteorology to “develop national guidelines for the development of a warning system for extreme heat events”

In the meantime, Douglas says, people are living in houses that are “unbearable”.

“During our summers you can sometimes see people in communities hosing the outside of their Besser brick walls with garden hoses to keep cool despite the water shortages – that’s how desperate they are.”

About 3ookm north-west of Alice Springs is Yuendumu, the largest remote community in central Australia. Its 900 or so residents are facing summer without a reliable supply of adequate drinking water.

The NT government has stopped building new housing because there isn’t enough water in the dwindling aquifer to accommodate more people.

Yuendumu is not alone.

The Central Land Council’s chief executive, Joe Martin-Jard, says that at every regional meeting, water security is top of the agenda.

“Between Alice Springs and Mount Isa, there’s probably only one major community with a decent water supply,” Martin-Jard says. “We’re not getting the rain we used to, to recharge the aquifers. So as water is drawn out of the aquifers it becomes more saline and less potable [drinkable].

“It’s a really horrible dilemma.”

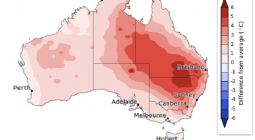

Water supply and quality issues in remote Indigenous communities

This map shows the location of communities in central Australia, highlighting those that have either poor water quality, are water stressed, or experiencing both poor water quality and water stress

The NT’s Power and Water Corporation, which is responsible for essential services in 72 remote communities and outstations, says most communities in the arid region are “faced with some level of water stress” and emergency planning is under way, but there are “rarely any simple solutions”.

“The difficult reality is that many communities originally developed historically in locations where there was never any secure, reliable, high quality water resources in close proximity,” a spokesperson said. “As those communities have grown … and expectations of improved levels of service have appropriately increased, the challenges also continue to increase.”

Power and Water says more drilling programs are planned but “finding new water sources is very challenging and often these drilling programs have moderate prospects for success”.

“Without large or extended rainfall … the water security risks will progressively increase in some centres, with an increased likelihood that source supply capacity at some could fail.”

At least 12 communities have reported poor quality drinking water. At Laramba, Willowra and Wilora, nitrates and uranium are at levels exceeding health guidelines. NT Power and Water says it is “investigating alternative technology options”. It has already installed treatment plants at Kintore, Ali Curung and Yuelamu to reduce high levels of nitrates, uranium and fluoride.

Air conditioning is essential in the desert’

In Alice Springs’ 18 town camps, where people from out bush often end up, houses are commonly built from Besser bricks – hollow concrete blocks which are cheap, but which trap the heat. There’s a lack of tree cover or other kinds of shade. Houses bake in the sun and, while the majority have solar panels, they often have only an evaporative air conditioning unit, known locally as a “swampy”, to cool the house.

A “swampy” uses a lot of water and can struggle on hot days, especially when there are a lot of people sharing a house, which is common in town camps with big families and fluctuating populations.

“Air conditioning is an essential item in the desert, not a luxury,” the CLC’s Josie Douglas says, “but it does not come standard.” When remote community and town camp tenants are offered housing, there is “a hole where the aircon unit should be and they are told to buy it themselves”.

“Many can only afford to ‘close the gap’ with a piece of wood, or run expensive reverse-cycle aircon very sparingly,” she says. “Some places don’t have enough water to use a cheaper swampy.”

Houses that don’t cool down overnight create big health and social problems.

“People resort to sleeping outside, or cramming everybody into the coolest room of the house, with all the well-known consequences for the spread of diseases that whitefellas only know from medical textbooks.

“It’s also common for people to sleep in shifts, with young people roaming the streets at night where they get into trouble, and sleeping during the day when they should be at school.”

This is at odds with the NT government’s view of the quality of town camp and remote community housing. A government spokesperson tells Guardian Australia that homes are designed with weather conditions and regional climate in mind, and they include external shading, natural ventilation and insulation.

“Investment into housing in town camps has included the installation of louvres, sunscreens, verandas and insulation,” the spokesperson said. “The Department of Housing and Community Development has also upgraded some key community infrastructure including improved shading and the installation of fans.”

Douglas is calling on the government to “stop building concrete hotboxes”.

“More than a decade ago, the government and the CLC were partners [in research] that came up with really solid recommendations about how to make desert houses more energy-efficient and communities more resilient.

“Some measures, such as making sure houses are built with the right orientation … and have passive cooling and a white roof, cost almost nothing. We would like to know how many of these expensive research findings have been implemented in our region.”

Shirleen Campbell is a Warlpiri and Arrernte woman who grew up at Hoppy’s Camp, or Lhenpe Artnwe. She told the Alice Springs climate rally in October that town campers were very worried about climate change.

“This is our place,” she said. “If it gets too hot, if we suffer through endless droughts or we spoil our water, then we don’t have another place to go.

“We want houses that are right for this place and right for our people. We want to invest in renewable energy, like solar.”

Campbell is a co-coordinator of the women’s family safety group at Tangentyere council, which delivers services to and advocates on behalf of town camp residents.

“Most of all we want people to treat this place as a legacy to be handed down to our children and grandchildren. It is not a speculative commodity and it is not something to be sold or exported.

“We have been here for a long time and want to look after this place for those that come after.”

Keeping cool in the library

There are few public places in Alice Springs to cool off. The Yeperenye shopping centre has security guards at the doors and, according to Douglas and Campbell, Aboriginal people are regularly moved on.

The library is a popular, free cool space. There’s a widescreen TV rigged up with headphones, showing movies. Westerns are popular, as are replays of AFL grand finals. The Saltbush room down the hall is a haven for older folk, while little mobs of kids hang out among the young adult stacks or cluster around the phone-charging station.

“We found there’s a gap in after-school care services from about 2.30 to 4.30, the hottest time of the day,” says the head librarian, Clare Fisher. “The kids can come to the library, cool off, have fruit and sandwiches.”

“Libraries are for connection and relaxation as well as knowledge. We make everyone welcome – but we explain how to use the library and how to behave as well. We very much believe in come and be who you are.”

Thirsty and dying animals culled

In January footage of dead and dying horses in a dry creek bed at Ltyentye Apurte, 80km south-east of Alice Springs, flashed around the world.

The Ltyentye Apurte rangers had the unenviable task of dragging more than 100 dead horses from the creek bed and disposing of their bodies.

In June the CLC conducted an emergency cull of more than 1,400 feral horses, donkeys, camels and cattle from a waterhole near Lajamanu. The animals were thirsty and dying, congregating around the last remaining springs and water sites.

The CLC has eradicated 6,279 feral animals in preparation for summer. Traditional owners don’t usually support animal culls, the CLC says, but there were no alternatives, with so many animals dying or in poor condition.

Feral animals damage community infrastructure and housing. Thirsty camels, for example, will attack air conditioning units because they smell water, and lay waste to water tanks, bores, fences, pipes and taps.

How hot is too hot? Heat, health and housing hotboxes

In town, Tangentyere council wants to measure exactly how well houses are functioning.

Tangentyere’s social policy and research manager, Michael Klerk, is in discussions with the CSIRO to install temperature data loggers in people’s houses, to build a case for improvements that are taken for granted elsewhere: solar power, insulation, better air conditioning, wide awnings, more shade.

“Last summer – which was a very hot summer, soon to be repeated – a lot of anecdotal feedback was that people’s evaporative air conditioners weren’t cooling the houses sufficiently,” Klerk says.

“This probably reflects the reality that evaporative air conditioners are not good at cooling houses when the external temperatures are in the mid-40s.

“You might drop the temperature of a house to mid-30s, but that’s not an optimal internal ambient temperature for comfort or for health.”

Most people living in town camps and remote communities, and some in suburban public housing, have pre-paid electricity meters.

Residents are issued a power card, which they top up with their welfare payments or income. Once the credit is spent, they have to top it up again, or go without electricity. Klerk says that happened a lot in the last quarter of 2018.

In Alice Springs, 420 of 570 households with prepaid electricity meters had at least one self-disconnection, which lasted, on average, 7.5 hours. Of the 570 Alice Springs meters, 285 are in town camp dwellings.

In effect, more than half the town campers ran out of money to pay for electricity.

“When the power goes off, it is bad for our health, the food gets spoiled, we can’t wash our clothes and we can’t wash our kids,” Shirleen Campbell told the rally.

“In summer, when our houses are hot or when we don’t have electricity, our people look for comfort in air-conditioned public places. We are not always welcome in these places and sometimes there are problems. We are thankful for places like the library and the pool.”

Klerk says low-income residents shouldn’t have to go broke trying to keep their houses cool. “It’s not acceptable that people’s houses are making them sick, and something really needs to be done about it. It shouldn’t all be passed on to the consumer.

“If it’s the case of people having to spend more money to keep the houses at a temperature that delivers health outcomes, then we have to rethink the levels of income support that are available to people, particularly in these regions where it’s so hot.”

Predictions by the Central Australian Aboriginal Congress for the health impacts of heat are dire. In its submission to the NT government’s climate change policy discussion paper, it outlined some of them: “Increased sickness and mortality due to heat stress, increased food insecurity and malnutrition, increased risk from infectious disease, poorer mental health and an increased potential for social conflict.”

‘The antidote to despair is action’

The Pintupi-Luritja artist Irene Nangala was among the first to return to her home country at Kintore in the western desert, near the border with Western Australia, in the early 1980s.

Until then, Pintupi people had been living a long way from home at the mission at Papunya, and they were homesick.

Nangala helped set up the Kintore school. It was a “windbreak school” at first, she says: just a tarp to keep the sun and the rain water out.

“Then we got a few teachers. It was hard work. We’ve got a proper good school now, proper shop. Nice clinic and aged care, child care.”

Nangala says she doesn’t have an air-conditioner. On hot days the family puts blankets on the windows. Other elders whose aircon units break down have to wait for a repairer to come from Alice Springs, more than 10 hours’ drive away.

“It’s really hot in Kintore. We can’t go and sit outside. We have to go at night to sit down with the families.”

Nevertheless, Nangala says she does not want to leave.

“We built up Kintore,’ she says. “People are really enjoying going back to their grandfather’s land. That’s the right thing to do. And it’s good for them to go back, the old people, good for the heart and the spirit.

“When they went first, they cried, they missed that place for a long time.”

Nangala says people don’t want to come into town, where life might be worse.

“Climate change is true,” Nangala says. “They [politicians] got the map and weather things, they should see the temperature what is happening around Australia, it’s so hot.”

Jimmy Cocking says: “We are walking blindly into the new climate reality. We’ve moved beyond hope, and we can’t be running on hope alone.

“The only thing that is going to get us over the line is action. And the antidote to despair is action.

“So there’s a lot of things that we need to be looking to change so that we aren’t going to be putting people’s lives at risk.”

17 December 2019

The Guardian