COP26: What effect does methane have on climate change? And more questions

The COP26 climate summit kicks off in Glasgow this weekend - one of the biggest ever world meetings on how to tackle global warming.

But what's it all about? BBC News environment correspondent Matt McGrath answers some of your questions.

What is the impact of the quantity of methane on climate change? - Maya Yossifova, Vienna, Austria

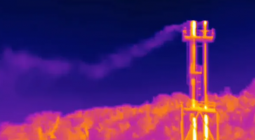

Methane is a greenhouse gas, which is released from both natural sources, such as wetlands and termites, and also through human activities such as agriculture, fossil fuel exploitation and landfill sites.

It's a compound of carbon and hydrogen, and this makes it exceptionally good at trapping heat - and a major cause of climate change.

According to the World Meteorological Organisation, methane levels in the atmosphere reached 1,889 parts per billion in 2021.

Concentrations of CO2 are roughly 200 times higher, but methane is calculated to be more than 80 times more potent at warming over a 20-year period.

A United Nations report earlier this year said that efforts to reduce methane emissions should be focused on reducing emissions from landfill sites and gas wells, cutting down food waste and loss, improving livestock management, and encouraging consumers to adopt diets with a lower meat and dairy content.

Are there any positive effects of climate change? - Mike Bell, Germany

There may well be some short-lived positive impacts to warming, but climate scientists have been quick to shoot them down because they are overwhelmingly outweighed by the negatives.

The most widely quoted "benefit" is the idea that a world with higher carbon levels will see plants grow faster and bigger. This is called the CO2 fertilisation effect.

However, research published last year suggested that this effect is already waning and any idea that it could somehow limit future warming is not supported by the evidence.

What confidence can we have of the impact of COP26 when the world couldn't even come together for an equitable distribution of vaccines? - Mahesh Nalli, London

There are parallels between the pandemic and the climate crisis, but some key differences as well.

As we've seen over the past 18 months, countries can keep Covid at bay by severely restricting the movements of people across their borders.

Such an approach doesn't work well with rising temperatures that are causing impacts for rich and poor nations alike.

While the question of vaccine inequity is likely to be solved by time and money, the climate crisis requires the rethinking and re-engineering of almost every aspect of our lives, from energy to food to clothing.

Ultimately the vaccine question is a short-term crisis, while climate change is slow moving and multi-dimensional.

Humans are reasonably good at sorting out one, but not so good with the other.

Is the global capitalist model not at odds with climate change and the need for a greener way of life? - Andrew, Exeter

According to some experts, such as the economist Lord Stern, climate change can be seen as the great failure of the market.

This is because businesses have not generally had to pay for the damage they have caused to the environment.

Global efforts to tackle climate change over the past two decades have focused more on harnessing capitalism to limit warming - for instance, putting a price on carbon and making the polluter pay, to ensure that emissions are ultimately restricted.

Meanwhile, it's also the case that if there's consumer demand for greener products and services, capitalism will try to meet that demand.

But there's evidently still a lot of work to be done to make these approaches work.

Does COP26 really need 25,000 people there? They will generate a lot of CO2, so why can't many elements be online? - David, Birmingham

The pandemic might be seen as the perfect moment for the UN to use technology for negotiations, and it was attempted during a preparatory meeting for COP in June, which ran for three weeks.

Unfortunately, it didn't go well - time-zone and technology challenges made it almost impossible for countries with limited resources, progress was limited and decisions were put off.

As a result, many developing nations have insisted on having an in-person COP. They feel that it is far easier for their voices to be ignored on a dodgy Zoom connection.

They also bring a lived experience of climate change that it is critical for rich countries to hear first-hand.

There's some evidence that this works. In 2015, the presence of island states and vulnerable nations was key to securing the commitment to limit temperature changes to 1.5C in the Paris Agreement.

30 October 2021

bbc