What Africa can learn from Kenya's robust energy policies.

Africa has one of world’s largest resources in reserves yet it accounts for more than half of world’s electricity deficit. The continent boasts about 12 per cent of the world’s crude oil and natural gas and 18 out of 35 countries with the largest renewable energy resource.

Yet more than 600 million people on the continent do not have access to electricity and some 730 million of them use unclean cooking fuel. And $32 billion is spent on cost, not opportunity, is spent annually to meet basic household energy needs.

Primarily the reason why Africa has the least electricity proliferation is that the continent also gets the least investment in private capital. According to data by the World Bank, Africa gets as low as one per cent of private sector investment.

This is relatively low even compared to other developing regions — 34 per cent for South Asia, 26 per cent for Latin America and Caribbean ( LAC) and 25 per cent for eastern Europe and central Asia. This low private capital investment has a direct correlation with government spending on and the state of energy policies and legislative framework. While bankable energy policies are available across the continent the investment risk undermines efforts to attract capital.

Africa needs an investment of between $70 billion and $90 billion annually to achieve universal access by 2030. By 2015 only about $10 billion was being invested, half of this from private capital and the other half from governments. Six countries among them Kenya accounted for 80 per cent of these investments, with some countries lacking any private capital at all.

In sub-Saharan Africa, Kenya was one of the first countries to liberalise its power sector, having allowed independent power producers(IPPs) to operate since the 1990s. Kenya’s energy sector is relatively well developed and has a strong track record. The legislative framework is conducive to foreign investment and is relatively well established for grid, offgrid and micro-grid projects.

In 2014 Kenya undertook a comprehensive audit of its Energy Policy Sessional Paper No. 4 of 2004, Energy Act of 2006, sector laws, by-laws and regulations and other policies. Through wide consultation as well as thorough situational analysis and assessment, a new draft national energy and petroleum policy was developed.

Today Kenya is one of the countries with the highest energy proliferation in sub-Saharan Africa. Electricity access rates rose from 36 per cent in 2014 to 56 per cent in 2016. Kenya is now on course to achieving universal electrification having launched the last leg of the “Last Mile” in December last year, which aims at achieving universal electrification by 2022. Under the programme some five million homes would be connected to the grid and additional 350,000 through mini grids. The programme, funded by the World Bank and Africa Development Bank (AfDB), is estimated to cost $2.7 billion.

Kenya’s energy sector has in recent years earned global ranking and recognition. Its geothermal industry is ranked ninth globally among geothermal power producers. In 2018 Kenya was third placed in terms geothermal power capacity, having added 29 MW from OrPower's Olkaria Plant.

Kenya is a now the second largest renewable energy investor on the continent after South Africa and is host to Africa largest single wind power plant (Lake Turkana Power Plant). In 2016 Kenya was ranked among the best renewable energy investment countries globally by Ernest Young’s Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index.

Until March 12, when President Uhuru Kenyatta assented to the new Energy Bill 2019, Kenya’s energy sector has been governed by Energy Act 2006. The Act consolidated Electric Power Act 1997 and the Petroleum Act Cap 116, and spelt out responsibilities for the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) and the Rural Electrification Agency (REA). The Act had also authorised IPPs to supply the national grid, although it did not adequately cover decentralised systems.

One of key policies that accelerated the pace of investment in Kenya’s renewable energy was the Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) policy that was introduced in 2008. The FiT instrument allowed power producers to sell renewable energy generated electricity to an off-taker at a pre-determined tariff for a given period of time, guaranteeing investors their profit margins.

Under the new law, the FiT will be replaced by the auction system that have become increasingly popular with governments as they seek to reduce consumer energy needs. For investors, auctions will still provide price stability. That said competitive auctions have proved to be highly effective elsewhere on the continent.

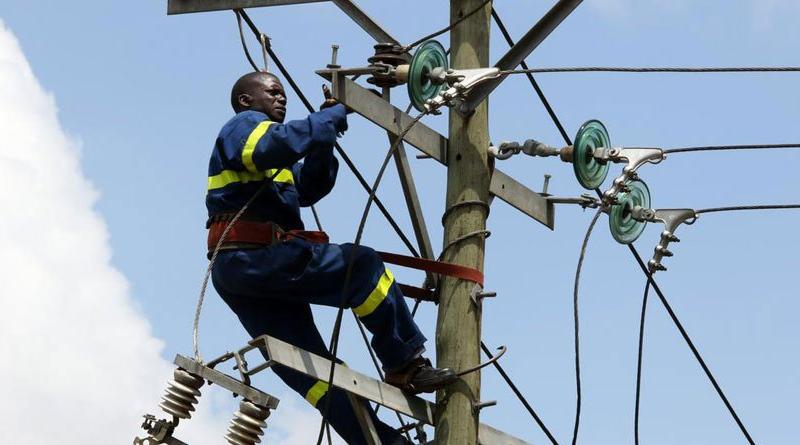

In power infrastructure, Kenya separated the functions of generation, transmission, and distribution. Power generation is undertaken by Kenya Electricity Generation Company (KenGen) and IPPs, while Kenya Electricity Transmission Company (Ketraco) does transmission and infrastructure development. Kenya Power undertakes distribution and power retail.

In about six years of existence Ketraco has built 1,000km of transmission infrastructure compared to 3,200km that had been built between 1956 and 2008. Ketraco's efforts have made it possible to offload new facility power from projects such as Lake Turkana Power Plant. It is currently implementing various projects to meet the 8,000km electricity line target in its Master Plan.

For geothermal power, the government established Geothermal Development Company(GDC), which undertakes exploration and steam development, offsetting the capital-intensive work and risk hence allowing investors to come in at more advance phases in steam production. This has spurred Kenya’s geothermal ranking , with an installed geothermal capacity of 630 MW.

In solar power, the government adopts a regulatory framework that deliberately favours solar energy development. Fiscal incentives include zero per cent on value added tax (VAT) for import of solar equipment and no restrictions or penalties for corporate adoption of captive solar. In 2012 Kenya also passed the Solar Water Heating Regulations that require all premises which use over 100 litres of hot water per day to instal solar water heating systems. As at 2017, the country was home to about 40 per cent commercial mini-grids operating across sub-Saharan Africa.

In financing projects Kenya has a robust and supportive policy framework, including the draft carbon policy and the climate exchange which facilitates carbon credits for financing renewable energy. By 2013 Kenya, a party to Kyoto protocol treaty, through the Clean Development Mechanism had earned $53.4 million in carbon from five renewable energy projects. In 2015 Nairobi opened Africa’s first Carbon Exchange. Kenya’s Carbon Exchange is modelled on Chicago and Australia. In early 2019 the Nairobi Securities Exchange(NSE) launched a Green Bond, the first of its kind in Africa, to finance green projects.

Currently renewable energy accounts for 87 percent of Kenya’s energy mix.

Nduta is founder, Extractives and Energy Network Africa. tina.nduta@eimaraafrica.com

7 April 2019